You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

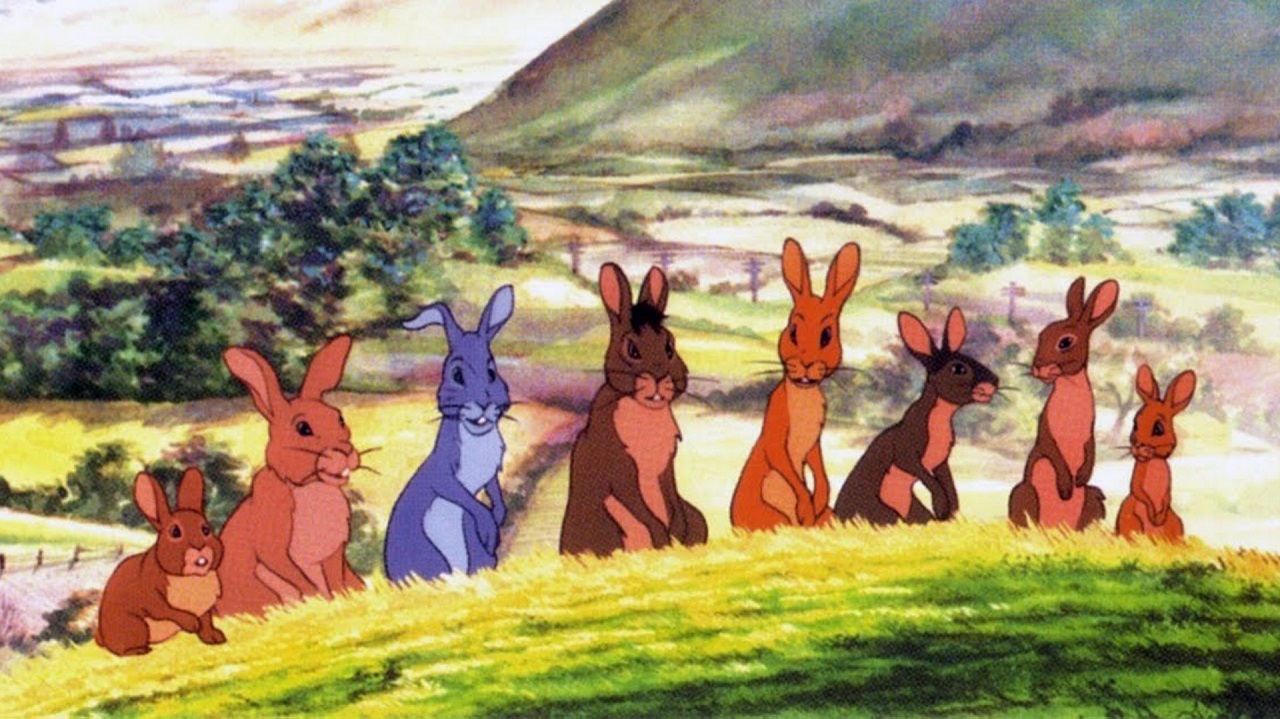

I recently watched Watership Down, the 1978 British animated feature following a warren of rabbits as they seek a new home, having fled disaster. I had seen it before, sometime in the early 1980s, in a format that I imagine modern children have no touchstone for: it just appeared on television one night, with no warning or fanfare.

Watching the film today, I impressed myself with how clearly and exactly I had recalled so many of its words and images. What really drove me to see it again, though, were freshly unearthed memories — bubbled up due to some passing stimulus — of the bus-ride to school the following morning, where the broadcast was all anyone could talk about. What had we seen? A completely unanticipated treasure dropped on us, utterly unlike any of the Hanna Barbera junk-food American cartoons we all ate daily. (And understand that, this being the past, a handful of TV stations represented the entirety of at-home video entertainment options for myself and my peers. We all saw this, together.)

I have no idea how wide that long-ago broadcast was — a national-network special, or just a local UHF station’s filler-content for the evening? Either way, I wonder how many professional animators or film producers sharing my age and city of upbringing began their careers that very night, electricity arcing from this unlikely story of animal life and death and failure and triumph and searing their spirit with a lifelong calling.

Today the film seems to retain equal reputation as a classic and an aberrance. In a funny coincidence, after mentioning my seeing the film to a British friend, they linked me to one of several local-to-them news articles about a recent airing of the film on UK television, and the outrage it engendered. The writers of these articles tend to cast the cartoon as nothing more than a source of cruel nightmares, focusing on the film’s shockingly frank scenes of red-in-tooth-and-claw violence and death. Of course I myself recalled well that aspect of the work, and how I felt quite disturbed by the film’s more subtle horrors — particularly the acid-nightmare imagery of Fiver, the scrawny and traumatized seer-rabbit, whose liquid, swirling visions of blood and terror set the warren on their flight.

But even more than all that, I remember the film as seeming very grown up, and not because of the rip-tear gore but because of its utter lack of condescension towards its audience. The intrinsic cuddly qualities of the small furry protagonists invite children to approach and watch, but the story sees them acting like adults. They clearly have goals and plans and live in a complex society, and at no point do they stop to explain any of it to the kids at home. It felt, in other words, like the real world did from a child’s perspective, but an entirely different world, and even better: a world within the real one, hidden, where the animals can talk, letting us listen in to their own animal-world ambitions and grave perils. I know that I found this absolutely riveting, at age eight, even if I couldn’t put into words why.

An example: there is a scene where the rabbits’ leader becomes caught in a snare, his confused struggles only drawing the cord tighter. Believing him near death and unable to save him, the others gather around in helpless shock. One of the rabbits breaks the silence, muttering something in a poetic meter, and after a beat his comrades solemnly join him in recitation. Today of course I immediately recognized it as a deathbed prayer to their rabbit-gods, and one that of course they’d all know by heart just from the rote practice that frequent death within their community would bring. I don’t think I processed all that as a child, because this was not among the details I had remembered. But I know that I saw it, and that it contributed to the literally other-worldy wonder I saw that night in front of the TV.

Among the scenes I did remember, almost word for word: the rabbits come across a paved road, an anonymous squashed critter by its curb, and have no idea what any of it means. One of the older refugees hops forward, recognizing the tableau for what it is, and tells the rabbits that they can cross safely with a modicum of cautious attention, for “the Hrududu runs along it”. Thus occurred my first unchaperoned exposure to invented language, even if only a trivial vocabulary, and without the thousand excited explainers that surround any utterance in Elvish or Dothraki that one encounters in today’s thrice-meta media environment. What delightful perspective that one scene zapped me with, all by itself, letting me feel so bright and involved for realizing all its implications on my own!

And the whole movie holds treasures like this, for a kid. In researching this blog post, I learn that a new adaptation appears imminent, and I’ve no feelings on that. I was glad to find the version I remembered very easily in my local pubic library — and held in the children’s section. On review, I feel safe calling this film a timeless achievement, and I hope that eight-year-olds will continue to stumble across it, utterly unprepared, for a long time to come.

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.