You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

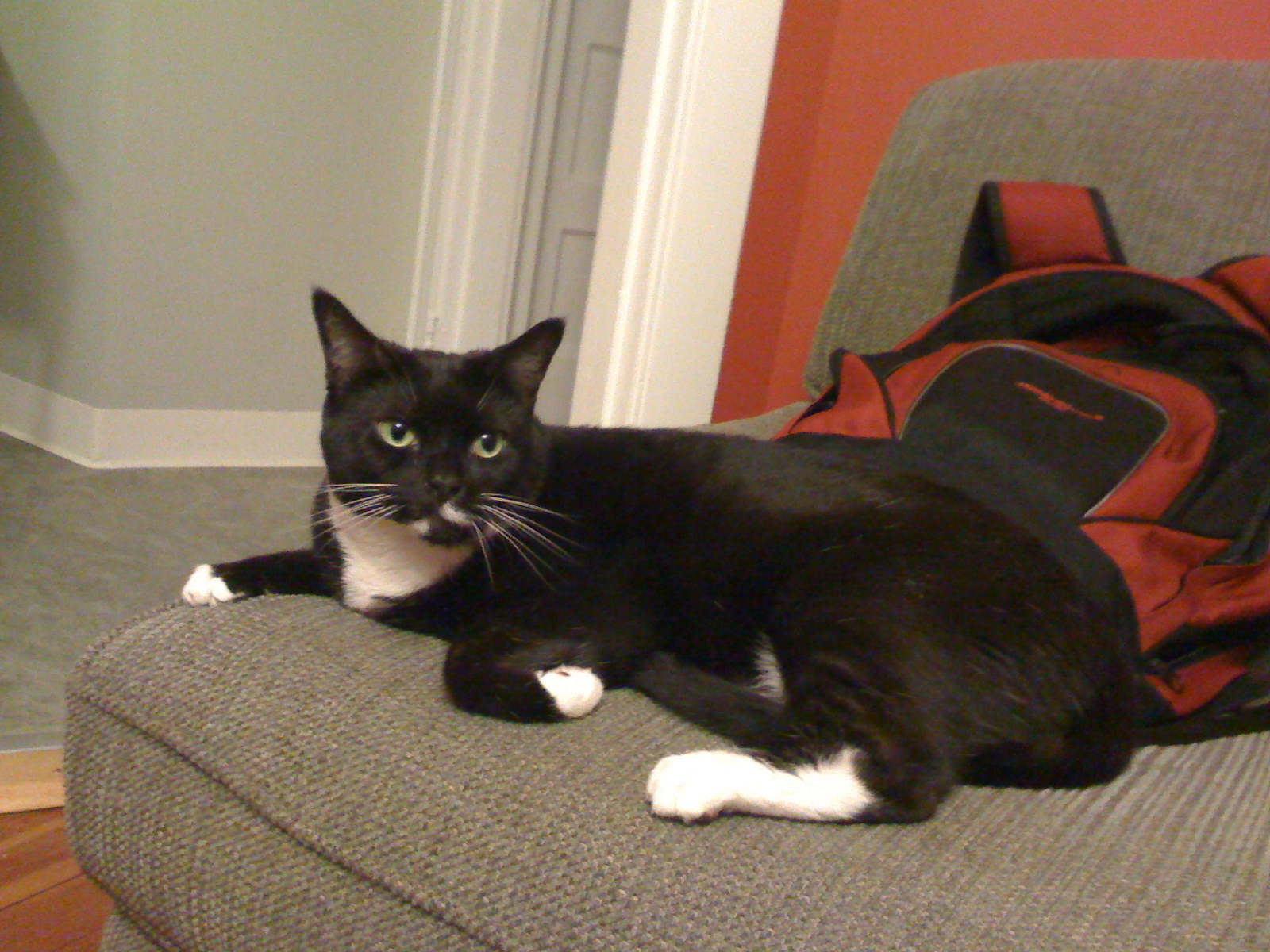

Ten days ago, my wife and I had our cat euthanized, hours after she started a clear and rapid decline from the heart disease whose inexorable progress we had tracked for years. For all those months, Ada worked around her own failing health, still taking interest in the usual cattish things even as her body gradually allowed for fewer of them. But on that last day, after an evening of avoiding eye contact with me while struggling through increasingly labored breathing, she padded into the kitchen after midnight, looked up at me, and meowed.

Something passed between us. I will always remember it. The memory of that ragged meow will forever live next to the memory of the soft animal sound my mother made when she saw my father for the last time, the cry of a creature that knows it has come to an ending. I woke up my wife and we put our coats on.

The presence of Ada’s absence lingers long, with a weight. When I round any corner of our little apartment, I subconsciously check around for the cat. If a coat is crumpled on a chair a certain way, my breath will catch. Just now I rose from bed to write this, because I couldn’t convince my whole sad brain that she didn’t lie on the mattress just out of sight, over the hill of my sleeping wife’s hip. I stretched out my arm to brush the cold, flat blanket there. Twice, at least.

Two days ago, at my wife’s request, I picked through every photograph I have taken over the cat’s lifetime, which is to say every photograph I have taken while my wife and I have lived together. These time-spans correspond. The task let me better understand why, perhaps, losing Ada has felt like such an ongoing ache. Whether we realized it or not, she was the mascot for the household my partner and I keep together, and the shared external spark we have carried with us through all our house-moves since then.

When I was twelve, we put to sleep Gi-Gi the dog, many years my senior and with whom I shared a best-case childhood-pet relationship. I recall the sadness of the day, and I also recall feeling like I had passed through a necessary ordeal of growing up. It felt natural, like moving forward. Losing Ada doesn’t feel like this at all. It feels only like loss, that a little animal so subtly definitional to our human relationship should leave us.

The first of the photographs depicts four-year old Ada a few days after we adopted her. It shows her moments after she first decided to stop cowering behind these strangers’ couch, and come lie down on the couch instead. The last photograph also shows Ada lying down, eight years later, but not alone. The three of us are tumbled into bed together, nobody at a flattering angle, an awkward composition forced by my urge to take a poorly lit self-portrait anyway, and only a month ago. You can’t see Ada’s eyes, but you can clearly see the shape of her black-furred head and face. A cat-eared negative space in the foreground, her two human companions fading into the back.

We’re not devastated. With plenty of foreknowledge, we prepared for her departure, and we’ll move on together as surely as I did after Gi-Gi. We have dozens more photographs between those two, which will assist with her life’s transformation into soft and happy memories. Today, though, and for a time more, I must allow Ada to exist, achingly, as a thing missing.

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.