You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

The first part of this post contains no puzzle or story spoilers for “Type Help”, but does discuss the story’s genres and mood. I include a warning before mentioning deeper spoilers.

I spent Friday afternoon and evening playing Type Help by William Rous. It’s very good, perhaps great. It’s the first game that I’ve played in eight years that gripped me in the same sort of way that Universal Paperclips did, and it seems likely that this game will join that one in my personal all-timer list.

Type Help names its deduction-game inspirations, including Her Story and Return of the Obra Dinn, on its web page, and these connections become clear as soon as you begin play. The game also reminds me a bit of the TV series Severance in that its frame story posits the existence of a science-fictional technology whose realism is both questionable and unimportant, and furthermore relies on in-world coincidences so profound that the story repeatedly lampshades their unlikelihood. But, also like Severance, the space that this sets up is so much fun to explore that all these rough edges are easy to wave away.

I do have to agree with Zarf, in his own non-spoiler review of Type Help, that for such a strongly written work, the title is so terribly weak. Combined with the cover art, the packaging unfairly makes the game look like either an office farce or a 90s-tech nostalgia trip, and not a period mystery with a horror infusion.

But that horror element is sublime. Zarf writes about how the puzzle-solving experience of this game gradually picks up speed as you play, until you’re positively racing to the meet up with the final scene. To this I would add that the discovery of the horror—whose nature is never explicitly spelled out—moves at the pace of an oily liquid you didn’t realize you’ve been soaking in for hours until you discover it seeping through your notes, pulling its terrible stain inexorably upwards and across your spreadsheet cells as you realize the truth of the narrative layered behind the puzzles. I found the implications of the story far more disturbing than a certain related game’s openly gruesome scenes of sea monsters gobbling up unfortunate sailors, and I loved it.

This carries a key similarity to Universal Paperclips, as well. In both games, you might begin play by thinking “Oh, one of these, I love these!” And you would not be mistaken: just like Paperclips is, in fact, a very good “idle-clicker” game and remains one until the end, Type Help is a solid “Dinnlike” all the way through. But fidelity to the source genre does not stop either game from getting weird, carrying you into truly surprising, even upsetting territory far beyond their respective genres’ expectations—while never needing to stray far from their minimal hypertext user interfaces. And this, more than anything, makes them great.

Before I talk about one or two spoilery things, I must also say with all due humility that I did completely solve this one with no hints, including the elusive “last lousy point” that Zarf wrote about. Putting an LLP into your game is an old tradition in IF, and I did enjoy seeing the ornery old bastard show up again here. (That said, there is at least one easter egg beyond the LLP I needed to be told about, and there may be others still…)

Spoilers from this point on!

Honestly, I just want to gush about how the pocketwatch was a phenomenal prop. It manages to be an homage, a total red herring, and a key plot device all at the same time.

Most obviously, the watch is a direct reference to Return of the Obra Dinn. (Another game that I enjoyed very much.) I was waiting for a character to mention how they heard that it’s an old family heirloom that once belonged to a maritime insurance adjustor.

And while nobody goes that far, characters do talk about it, quite a bit. They fob it back and forth, hide it, steal it, hide it again, die while holding it, and subsequently loot it. Some characters start overtly fearing it as supernatural, which naturally leads the player to start suspecting it too, and to pay close attention to its movements. In my spreadsheet that tracked the characters’ locations during each time code, I added a little “⏱️” emoji to every cell corresponding to the watch’s shifting location and possessor.

And none of that matters, because the disaster that powers the story has nothing to do with the watch. And yet! Paying close attention to how the characters react to the watch, especially their increasingly confused reactions to it as time ticks rightward and the thunderclaps come faster and faster, can play a key role in helping the player to understand the true nature of the horror. While the first big, unmistakable reveal about the curse’s true nature happens during Helen’s confrontation with Eddie and subsequent demise, the watch provides an important “checksum” for understanding various other, finer details of it over the next few hours of play. In the end, I welcomed the watch’s utility to help solve the mystery, even though it absolutely tricked me and led me all a-ticktock down the wrong path first.

So, so good.

Anyway, the game should have been titled I’d Climb The Highest Mountain, right? Or some derivative of that. Let ‘em wonder until the end. Or even The Hangman, get a little Agatha Christie up in there! Seriously.

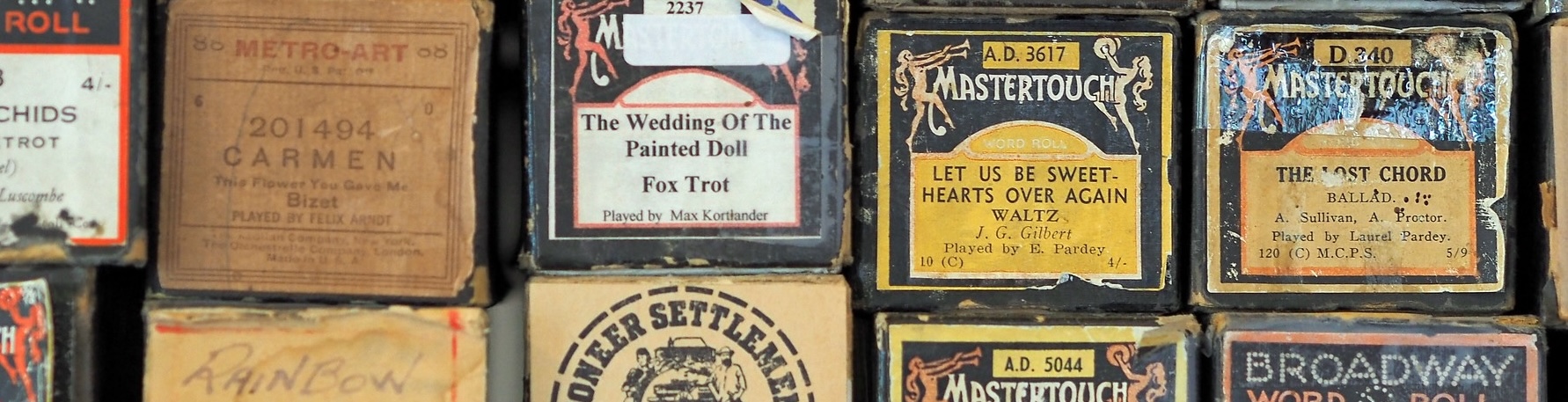

“Piano Rolls” by Kaptain Kobold is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 .

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.