You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

This summer I developed presbyopia, or anyway had my genetically predestined presbyopia develop to the degree that compelled me to seek out and read the web pages that taught me the word “presbyopia”. With here-yesterday, gone-today suddenness, I have — forever, it seems — lost the ability to focus my eyes on any objects closer than the length of my arm. My visual world, once an unbroken bubble extending into the infinity of space, has developed a lacuna: a tiny sphere of uncertain blur immediately surrounding my own head.

I came to enter my symptoms into a search engine because I quite honestly had no idea that this happens to everyone, or at least everyone with typical eye-function who lives long enough. Apparently one usually becomes a candidate for the condition in one’s mid-thirties, with a near-certainty to obtain it before you turn fifty. At age 45, then, the near-focus fairy seems to have visited me right on schedule.

This happens as I adjust to exercising more than ever and shoring up my diet in a bid to — putting it frankly — do better than my father (and his own father) at dodging the heart disease that my family history predisposes me to. Insofar as I’ve responded to my own physical aging, it has taken this form: getting serious about resisting the inherited threats I’ve long expected. And that’s all fine.

In my zeal to sweat these dangers away, though, it seems I spent no time at all learning about various inevitable robberies of aging that visit nearly everyone who pass various milestones, once they’ve rolled on beyond the easy pavement of young adulthood. Presbyopia has stricken nearly every human who has survived to middle age, and yet it was news to me. Definitionally, the list of people who live with this condition include several friends of mine, who upon hearing my complaint rolled their already long-blighted eyes and advised me not to let pride delay getting some decent bifocals.

(I have not bought any bifocals yet. The last pair of glasses I purchased have the sorts of skinny frames quite fashionable in the early aughts. They let me achieve a poor-man’s bifocal effect by tilting my head up and peering beneath the lenses, since my uncorrected eyes can focus on objects as close as elbow-length. I recognize that I’ll want to do better than this, someday.)

I can grimly appreciate that while I strive to blunt and delay, with diet and exercise, the ever-increasing incline of age that otherwise saps the energy, flexibility, and mental acuity that burble in abundance through one’s first decades, there exists an irrestiable schedule listing one self-contained anatomical system after another that must succumb to accumulated entropy. Had I somehow pushed my resting heart rate down below 50 beats per minute, had I dropped all red meat and sugar from my plate years ago, my eye-lenses would still have flabbed out exactly as destiny decreed.

I can’t help but wonder what other unhappy events might lurk on this ordered checklist of personal systemic wrap-ups. Maybe I’ll actually look, sometime; surely this knowledge has existed more or less unchanged for centuries, maybe millenia, and I suppose it just doesn’t come up until one arrives at it personally because who wants to talk about that? More likely, though, I heard references to these events my whole life and didn’t pay much attention. That has changed: In the opening of his new essay collection Calypso, David Sedaris chooses to describe his current age by noting, with characteristic frankness, how his urinary “washer” has recently given up, permanently adding unwelcome complication to his bathroom visits. Last year I would have given an amused snort and forgotten the passage. This year it made me a little dizzy.

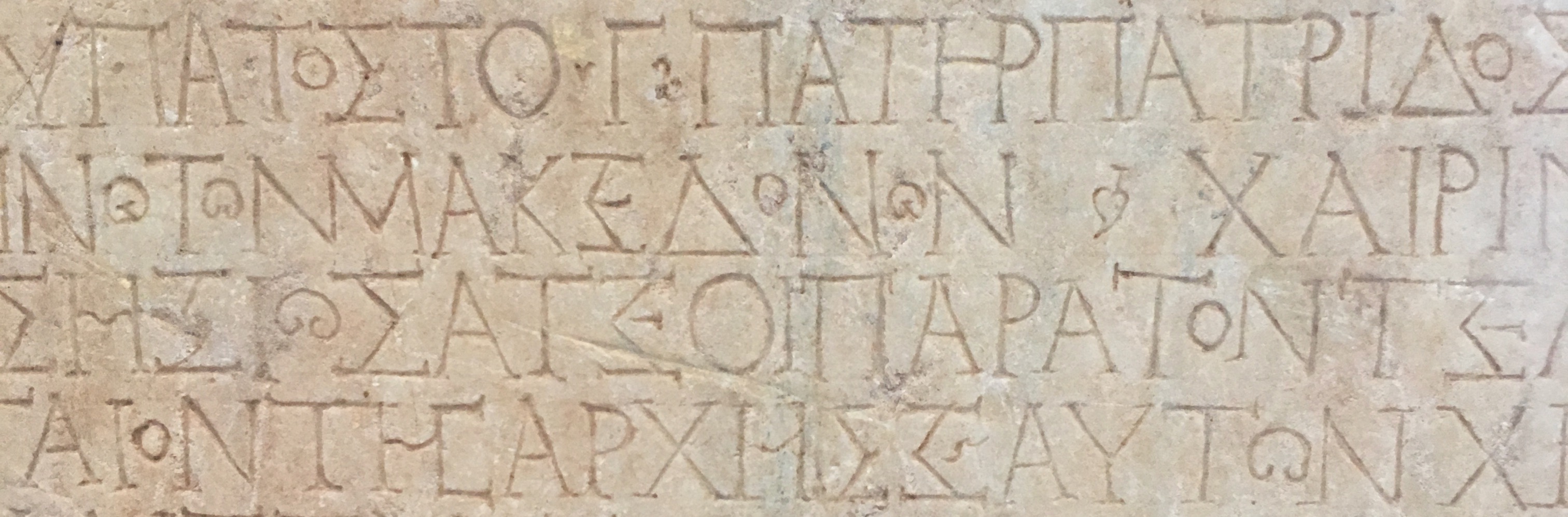

Two years ago I visited the RISD Museum for the first time, and I encountered one particular artifact from its permanent collection: a slab of ancient white marble, chiseled all over with Greek writing. The plaque affixed by it noted that it still retained a very few flecks of the red paint that originally tinted its beautiful lettering. Forgetting my place, I could not resist putting my face right up to it, eager to see the paint for myself. Within seconds, of course, a watchful docent had a hand on my shoulder, a surprising gesture that flash-froze the whole scene into my permanent memory.

And because of all that, that slab became my most recent — and therefore final — definitive memory of looking at anything close-up with my naked and unmodified eyes. I suppose I should take a philosophical view, making metaphorical my new obligation for far-sightedness, appreciating that I got to enjoy supplely youthful eyes for as long as I did. Wikipedia says that written references to presbyopia appear as far back as Aristotle, and I find that oddly comforting. I can treasure my memory of the carved letters, a memento from a time and place long ago, and the arcs of time it represents both personal and civilizational. If I have to put a little more distance between myself and the things I contemplate, so be it. I will trust that the paint is there.

Photographs in this post by the author.

Next post: UMaine, please deplatform the College Republicans

Previous post: Let’s rename “the 7-minute workout” to “the Klika-Jordan workout”

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.