You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

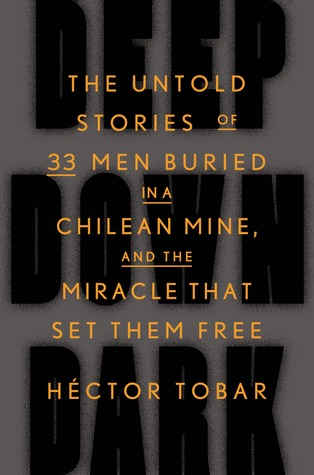

I learned about this book in a pleasantly indirect way. A review of Héctor Tobar’s most recent novel in the New York Times offhandedly mentioned his earlier and much-lauded Deep Down Dark, a 2014 account of the harrowing ordeal and miraculous rescue of the 33 trapped miners in 2010. “Well that sounds good”, thought I, and had a checked-out ebook edition from NYPL on my phone within the minute, while waiting for an eye-doctor appointment. Not bad!

I learned about this book in a pleasantly indirect way. A review of Héctor Tobar’s most recent novel in the New York Times offhandedly mentioned his earlier and much-lauded Deep Down Dark, a 2014 account of the harrowing ordeal and miraculous rescue of the 33 trapped miners in 2010. “Well that sounds good”, thought I, and had a checked-out ebook edition from NYPL on my phone within the minute, while waiting for an eye-doctor appointment. Not bad!

I remembered the rescue, of course, but knew very little of its details. I had watched videos of that purpose-built elevator on Twitter. I read shortly afterwards that the miners had told media that they’d agreed to a mutual secrecy pact about what had transpired during their weeks trapped in the earth, and I recall that same media assuming that this meant their experience was simply too terrible to tell. So, learning that an entire book had appeared just four years later, compiling interviews with many of the miners and their families, really stirred my curiosity.

Deep Down Dark reminded me of how much I love to read these sorts of moment-by-moment accounts of disaster that focus on how the people caught within manage to pull themselves through via resolve, ingenuity, and mutual support. And in this case, one key to all the miners’ survival was the fact of their great number, which meant that they had many incidental skills among them that benefited the whole group. It read like a gripping post-apocalyptic novel about a small group of diverse people banding together to survive, but without the unnecessary baggage of zombies coming to eat them, or any betrayal from within.

Tobar introduces us to each of the many miners he collected stories from, as they depart their respective homes around Chile or Bolivia and make their respective ways to the mine for their week-long shift. That primes us with a strong sense of their different backgrounds by the time the disaster happens: a skyscraper-sized mass of stone slicing guillotine-style through the mine, sealing away everyone who happened to be working or resting within one particular section of the mine’s downward-spiral ramp.

Dislodged, too, was my vague idea that the thirty-three men had done little but await rescue in the bottom of a dark pit, crammed together in a single filthy shaft and surviving through an unimaginable miracle. The true story of their subterranean situation is of course so much more complicated and interesting. For one thing, the trapped miners still had access to a sizable length of mine: a long, curving main corridor blocked at either end by that fallen slab, with a number of side tunnels and chambers, including a little kitchen area. They also had several vehicles with them, capable of moving heavy loads, and various pieces of large mining equipment that they could strip for parts and (dirty but emergency-potable) water.

After the shock of the mine’s collapse, they took stock of their situation, and as a group planned how to use their incidental but real resources to survive as long as possible, while keeping up hope that the rescue-drills would find them. Among their number was an electrician who set up dim but permanent lighting, from scavenged headlamps and vehicle batteries; a man who had nursing skills from taking care of his ailing mother; a natural jester (and clearly Tobar’s favorite interview subject) who kept everyone’s spirits up, and who encouraged another miner with a side-gig as a preacher to commence daily prayer gatherings. And one miner had the skill maybe most crucial to the book’s existence—an affinity for writing, enough that he kept a detailed journal of the adventure, even during the darkest times when he assumed its readers would find it by their long-dead bodies, if ever.

Their story enters only its second half when the first drill-bit of the rescue teams breaks through their prison, after which all the miners become worldwide celebrities with high-speed internet access and dreams of ongoing wealth and fame, even as they remain stuck inside a mountain with no clear route of escape. And this, it turns out, lay at the heart of their code of silence: not that their adventure was simply too awful to relate, but that they all agreed to carefully control its telling, with no single miner claiming any exclusive rights to it. The miners went as far as requesting a lawyer help them draft paperwork for all to sign prior to their emergence, sent to them via pneumatic tube. Even after they returned to their homes and families, the thirty-three remained bound by their shared story, not as mere memory but as a living pact they made together and whose revelation would happen only when they once again all acted together; which, in a few years’ time, they did.

Now’s as good a time as any to have read a true story about people thrown into a dark and terrible situation and managing to not just see each other back into the light, but follow through, so that none became forgotten afterwards. This book’s pretty great.

This article was also posted to the “books” section of Indieweb.xyz.

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.