You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

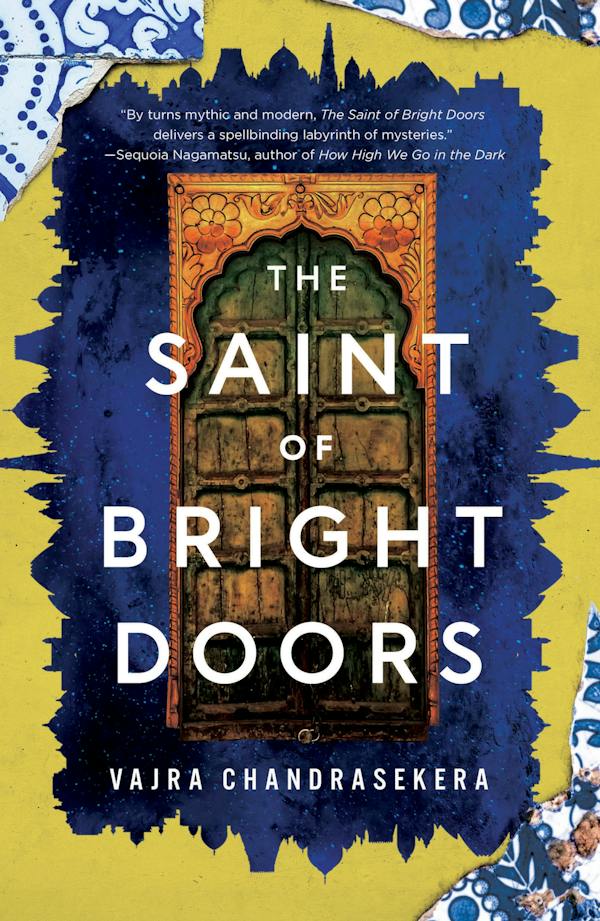

The prologue of Vajra Chandrasekera’s The Saint of Bright Doors reminded me of Robin Hobb’s Assassin’s Apprentice. Here is poor Fetter, a small child with supernatural gifts and uncertain lineage, raised to be a cruel killer. But after a time-jump to meet young-adult Fetter in the big city, it becomes something more like The Tick. Fetter takes breaks from his gray-market job as a community fixer for the immigrant-swollen slums to attend a support group for “unchosen ones”. These are unfortunates born to be world-altering messiahs, but who either ditched the path or got bumped out of it through dumb luck.

In Fetter’s case, he has no shadow, can ignore gravity at will, knows the secret songs that sharpen knives to murderous efficacy—and is fated to slay his father, the beloved and possibly immortal leader of his land’s most prominent religion. But as soon as young Fetter got a taste of city life, he decided to just forget about that last bit. In the world of Bright Doors, this sort of background is common enough to merit a standard designation code on citizen ID cards, alongside race and caste classifications.

Fetter struck me, around this point in the story, as a Philip K. Dick protagonist: a good-hearted nebbish living in a weird world and possessing uncanny powers, but still a nebbish. Of course, you can’t have Fetter’s history and hope to life a peaceful life forever, and soon enough his adversary arrives—who is absolutely a PKD antagonist, straight out of Ubik, someone can edit reality at a continental scale to suit his needs. You need to understand that this is praise from me! I have been thinking lately about how Dick’s fiction fits into these strange days, and was predisposed to see these correspondences. But I am very happy that I did.

Details: I love the way this antagonist doesn’t so much remold time and space as smear it, smushing passes through mountain ranges by speeding up erosion. This requires the wrenching apart of two consecutive moments by millenia, forcing whole histories to swirl in, uncontrolled, to fill the void, like the start of a Dwarf Fortress game. And for all this, the narrative points out that the religion he heads will never become more than the fourth- or fifth-most powerful in its world, if you take everything into account. The world of Bright Doors, like our world, is still a very big place, even for demigods.

Fetter’s corner of his fantastic place evokes the Indian subcontinent, and perhaps Sri Lanka in particular, in both geography and culture. It melds supernatural intrigues, like Fetter’s “unchosen” crowd and the eponymous bright doors—delightfully weird artifacts scattered around the city, and the object of Fetter’s growing obsession—with social media and crowdfunding campaigns. The city bustles with life and art, and trembles under the growing presence of militarized religious orders led by TV-celebrity monks in saffron robes. Inevitably, the winds rushing from those bright doors sweep readers past breathtaking betrayals and reversals and into a kind of uncertain apocalypse, one that allows Fetter to meet the demands of fate while rejecting the chains that would bind his name.

I loved this novel, and can recommend it to anyone.

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.