You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

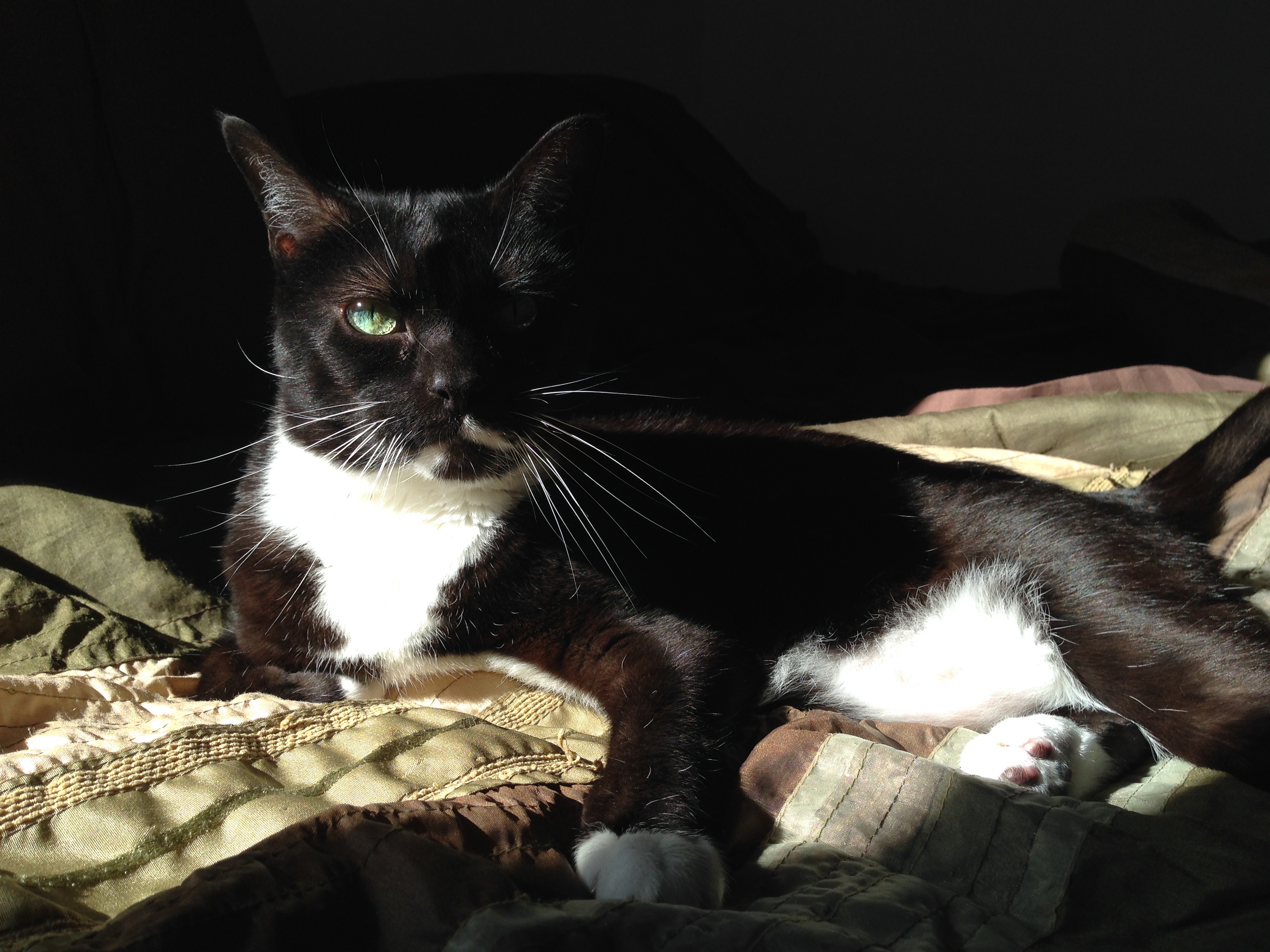

Received The Last Guardian from a thoughtful in-law for Christmas of 2016, but put off playing it for many months. I had played the two previous major works of Team Ico, and so shared the expectations about the game’s emotional ordnance that had preceded its release by several years. Given our family loss immediately after the holiday, my wife and I did not feel ready to face this game, which centrally features an enormous, cat-like companion that we knew we’d unavoidably feel a real bond with — because Ueda and company are very, very good at what they do. We knew also that this would make ourselves vulnerable to real-enough sympathetic trauma, far too soon.

We made the right choice. The Last Guardian simulates the entire emotional journey of life with an adopted pet, accelerated to video-game speed, and with its natural drama and danger inflated proportionally to match the creature Trico’s two-story height. To accomplish this, it presents not just a believably simulated animal, but an illusory animal mind, and then requires the player to build their own heterophenomenology of it — their own internalized model of the creature’s subjective world, in order to communicate well enough across the human-animal barrier to navigate the objective game-world together. It succeeds so well. I’d never experienced any fantasy quite like it before.

Your journey with Trico takes you from initial wariness through growing trust as you both gradually explore how you complement one another beyond merely trading amusement for food. (Granted, there is that, too!) This carries low moments along with the high ones. The shared pain when the pet gets hurt, the worry when it gets sick. The animal surprising you with its own kind of concern and sympathy when you fall ill or injured. The frustration when, no matter how strong your bond may become, you find things you just can’t communicate to the companion who has put all its trust in you, and do your best to cope. It’s all effectively represented here, and I found myself extremely willing to believe in the mind of the enormous, cold-nosed, muscular Trico, his thoughts slow, earthy, but undeniably present.

Once it forges the link between beast and boy — and, by extension, to the player as well — all the game’s emotional high and low notes feel stunningly amplified as they reverberate along that bond. In-game moments of pain and fear cause real anxiety, exactly as we’d expected. This applies even to minor beats: whenever the boy needs to slip out of Trico’s view for a bit, the creature howls its worry at the separation, and my partner and I in our living room would act exactly as we would if our cat started had moaning two rooms away. In fact, we — I, especially — would semi-consciously talk to Trico constantly, reassuring him (and his big soft wet eyes) when we re-appeared, and singing the food-food song I used to sing for Ada whenever the boy returned bearing a treat for him. (There is, in fact, an in-game “pet Trico” verb, always available but mechanically necessary at certain parts of the story, and I dare any player to not vocally soothe the on-screen creature while using it to calm him.)

The game increases the emotional stakes in the early mid-game when it becomes clear that Trico had suffered abuse earlier in his life. Even as I type this I feel a lurch of emotion to recall this realization dawning on me, gradually, over the first hours of play, and we found ourselves learning to recognize and work around the animal’s trauma-remembrance triggers. I remember, too, the disgusted outrage I felt when the game’s villains start to actively exploit these triggers against poor Trico, and the angry triumph that welled up when he and I would find ways to fight back.

Due to all this, we needed at least six months of calendar-time to proceed through the whole game, even though the experience involves a few dozen hours of gameplay at most. My wife and I would push ahead in Trico’s world, with all its strains and obstacles, until the cumulative stresses stacked up to a shatteringly fragile degree. And then we’d take a few weeks off. Trico would wait for us, and greet us with relief when we felt ready to return, and we’d venture on a ways further.

As dizzying as its low points get, the game’s emotional high points soar. The fantastic setting allows for a literal spin on the classic “Who rescued who?” animal-adption bumper sticker, with more than one moment where you reach for Trico in desperation, and he reaches back with teeth or tail to pull the boy to safety. Besides these incidents, though, the game’s ongoing proof of its central human-animal bond serves also as perhaps the game’s most underappreciated facet: The Last Guardian contains the finest verisimilitude for riding an animal that I’ve had the pleasure to play.

While the little player-character can clamber around on Trico’s thickly feathered back from the get-go, he gains the ability to direct the big animal’s movements only later in the mid-game. And I mean direct literally: you can tell Trico where to go, though voice and gesture cues (themselves generated by certain stick-and-button combinations), but it’s up to Trico how — or, indeed, whether — to interpret your instructions.

If you tell Trico to trot across a wide room or down an open corridor, he will generally pad along in the direction indicated. But request a more complicated or dangerous maneuver, and Trico takes his time. Not out of stubbornness, though it may seem that way at first. Trico will look in the direction the boy points, and flick his ears, and pause. Maybe he’ll sit on his haunches for a bit, while considering the flying buttress or crumbling pillar you’re asking him to leap atop. But then: he shuffles to a calculated position, bunches up his muscles, and launches, carrying the whooping boy who grips his pelt, and (usually) sticking a graceful landing.

After a while, I came to feel like I knew how to not so much drive as accompany Trico through the stony, airy fortress that you together pick your way across and up. This experience felt worlds different not just from the many in-game sections where the boy must climb and jump around by himself (while Trico watches, groaning in worry), but from literally every game I’ve ever played where the player-character mounts a horse and proceeds to treat it like a jeep made of meat. In other video games, mounting a horse (or a dragon, or a war-bear, or what have you) instantly re-wires the controller directly into the brain and muscle of the animal, and you proceed to simply trundle it around effortlessly. Guardian’s approach of keeping the controls always focused on the boy, even during times when Trico carries him, reinforces the game’s core theme of animal companionship. It de-emphasizes control in favor of communication, of the certain kind of communion that only happens between a bonded human-and-animal pair.

The Last Guardian asks a lot of trust of its player, for a level of emotional investment that leaves the player feeling uncannily vulnerable. By the end of the game, I felt very glad I gave it my trust, even as I also felt glad for waiting until I stood on firmer emotional footing in real life.

Next post: We can reclaim the second amendment from the NRA

Previous post: I played _Nier: Automata_

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.