You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

Following up on my last post, I finished reading Wuthering Heights over my Christmas vacation. I find myself not just with a lot to say about this book, but with the complexity of my thoughts fanning outward most pleasantly as soon as I start writing them out. Accordingly, I’ll try spreading my wandering Wuthering thoughts over a few Fogknife posts, rather than try to mash everything into a single meandering essay. (Here I take a page from Todd Alcott stepping through his Star Wars thoughts, with no promise to be that interesting.)

None of these posts will hesitate to spoil deep plot details. Yes, yes, spoiler warnings for a 170-year-old novel, o merriment. Look: I didn’t know what was going to happen, and the ancient story managed to surprise me again and again just last week. What’s more, the critical introduction of the edition I read had the good grace and modern sensibility to lead with a wonderfully British reader advisory of plot disclosures as well. Anyway: you should read this book, it’s pretty great.

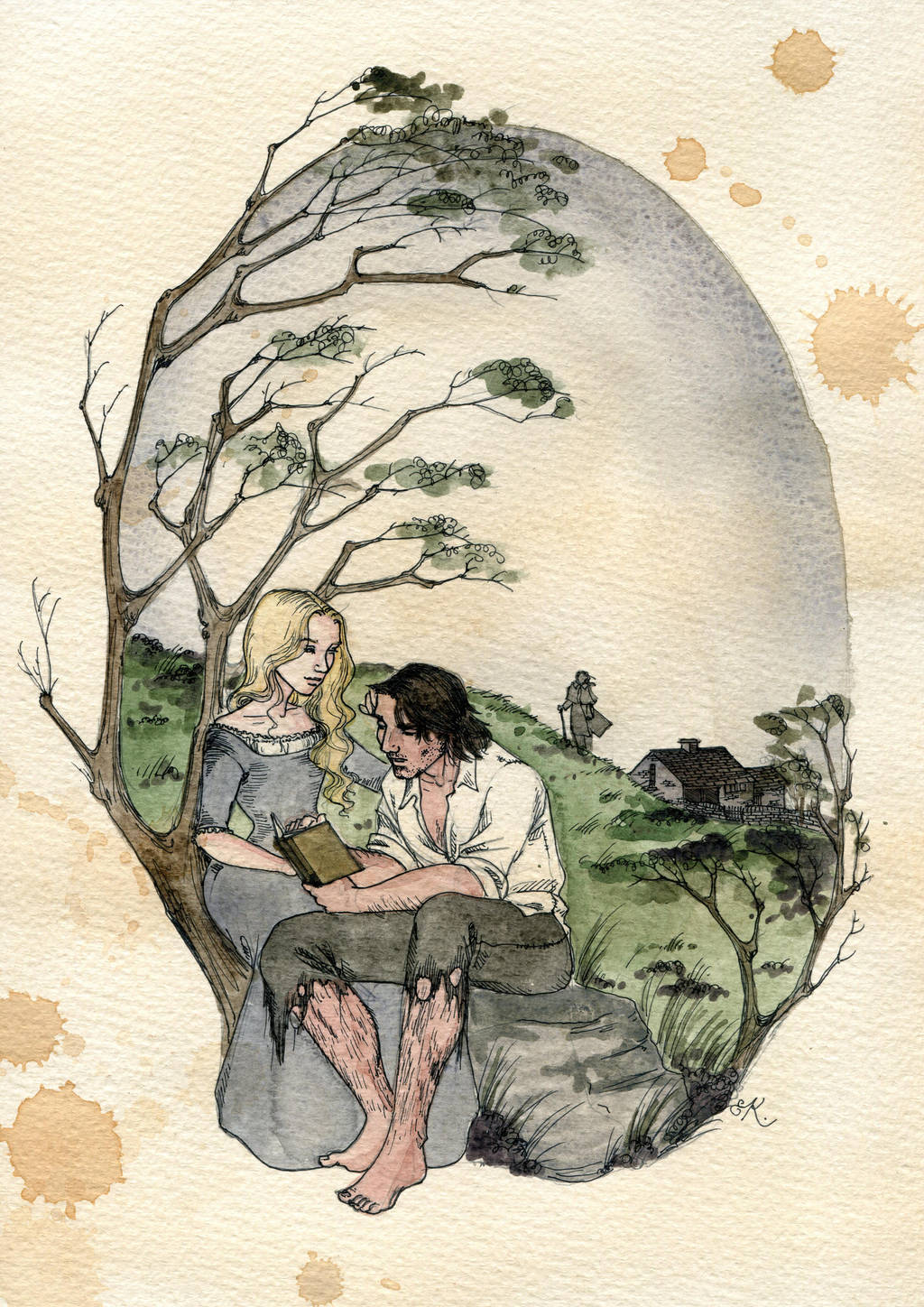

I found the landing place of the younger Cathy, one of the story’s few survivors, both beautiful and troubling. I can appreciate the grace and light that she brings to the ending with via her rescues of both herself and Hareton from Heathcliff’s terrible machinations. But as a modern reader, I had difficulty finding justification for her falling in love with crude Hareton so fully and so swiftly. My brows knit when Lockwood spies the unlikely couple smooching by the window, and Nelly’s subsequent three chapters of explanation didn’t really satisfy me in this regard. It seemed to play into stereotypical expectations of the feminine obligation to fix broken boys, uncomfortable even given the period setting.

Thinking it over for the sake of this post, though, I can’t help but convince myself of this improbable romance’s plausibility. Heathcliff had essentially imprisoned both kids, after all, and Cathy acted out of canny self-preservation to turn Hareton against his foster father so that they might both go free. As a prerequisite, Cathy had to pluck out the poisoned thorns that Heathcliff had spent years squeezing into the poor boy’s heart, and this in turn required a lot of patience and a degree of intimacy. Hareton becomes Cathy’s project, then, the one thing keeping her focused and hopeful in the dungeon that Heathcliff had made of Wuthering Heights. Under those stressful circumstances, who can blame her for slipping up a bit, and letting this necessary project-passion boil over into romantic love?

Still, it seems a shame that Cathy should marry the young dope, pledging to spend the rest of her days with him when both their lives, finally free, are only just beginning. But another only-now realization comes to my rescue: it’s dear old gossipy Nelly, and not Cathy herself, who describes the kids’ friendship(-with-benefits) as altar-bound. Yes, she tells Lockwood that they’ll tie the knot on New Year’s day, and yes, every Wuthering genealogical chart I’ve seen — including the one prefacing my 2003 Penguin edition — takes Nelly at her word, drawing a horizontal marriage-line between Cathy and Hareton. But I say: Not so fast.

In the text, Lockwood tells us that he pays his final visit to the Heights, where Nelly glomps onto his ear to relate the final act, in September. That would put a New Year’s wedding more than three months beyond the conclusion of the text. Therefore, I have all the wiggle-room I desire to imagine my own epilogue: now free to move about the land a bit, Cathy visits Gimmerton village and meets literally any other human being and starts to re-examine her options a bit. Maybe it gives her a taste for travel, and she rambles on down to examine her story’s own origins in Liverpool, the mysterious city that had coughed up Heathcliff some 30 years prior.

You don’t need to rush this, Cathy! Go take a little break, stretch your legs, you’ve earned it. And don’t worry about leaving Hareton at the Heights; if it turns out that you want to come back to him after all, I have every confidence you’ll find him waiting there. It seems quite doubtful that it’d even occur to him to wander off anywhere else.

Next post: Wuthering Heights: Lockwood’s reality

Previous post: I am reading Wuthering Heights (and works adjacent)

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.