You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

In the introduction to the 2003 Penguin edition of Wuthering Heights that I read last month, Pauline Nestor describes the book’s world as dreamlike, limiting itself to only two locations and the stretch of moors between them. The whole rest of the world seems to exist in a fog. Characters don’t travel abroad so much as vanish uncertainly, later emerging from the mists rather than merely returning. Even the neighboring village of Gimmerton, ostensibly significant in the characters’ lives, receives only the vaguest definition.

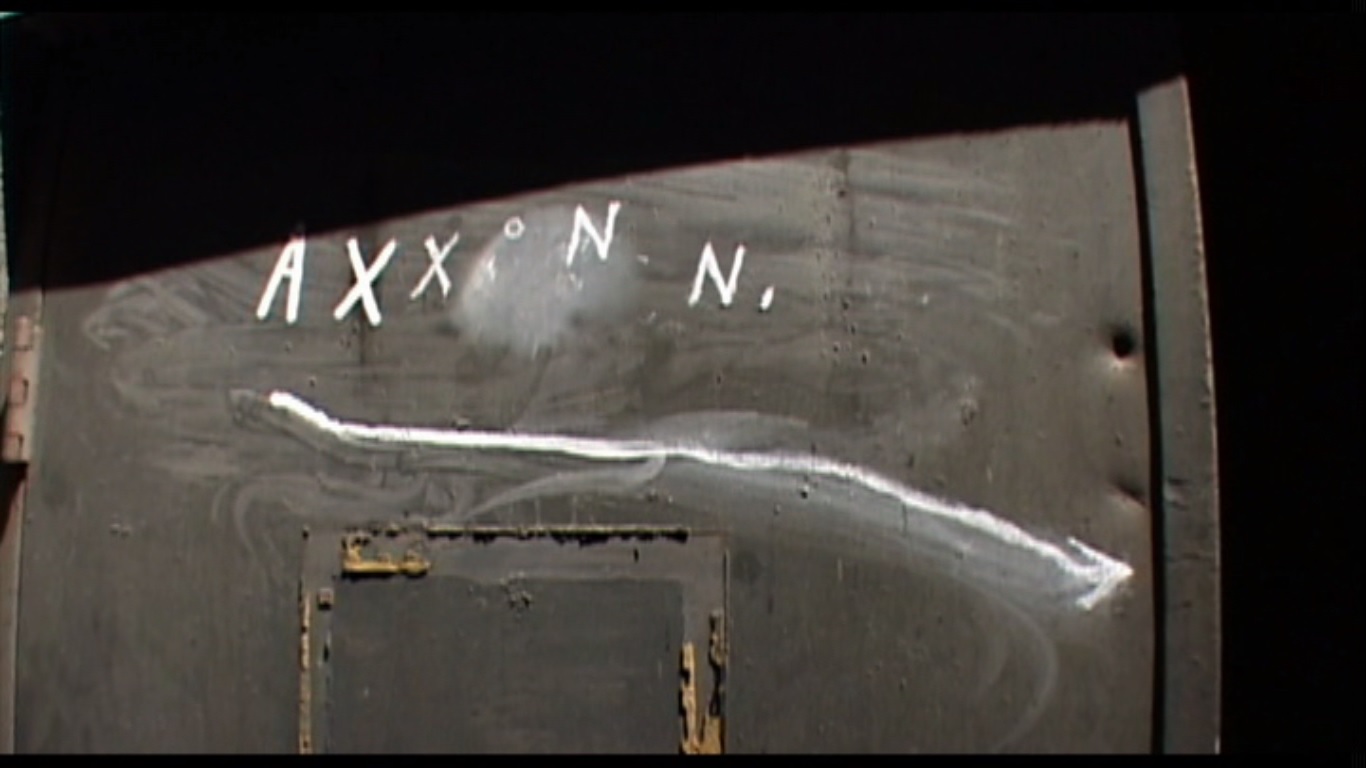

This resonated with me because of the positively Lynchian aspects of Wuthering Heights that struck me towards its conclusion — especially when considered from the perspective of Lockwood, the narrator managing the outermost of the book’s nested frames. He reminded me, by the end, of Laura Dern’s character in Inland Empire. Both of them arrive at their respective stories as perfectly relatable and literal point-of-view characters. Within a few scenes, though, things suddenly tip into the dreamily strange, and the characters seem to lose their place amongst narrative layers; both must struggle to find a right-side-up ending that doesn’t obliterate them completely. Dern’s character may have a much more overtly surreal and unsettling journey than Lockwood does, but I can’t resist using it as a lens to re-examine Brontë’s work just the same.

As far as I can tell, we as readers end the book knowing almost nothing about Lockwood personally. He makes clear through repetition that he lives in London normally, and he tells Nelly that he leased the Grange for a year on a whim. This — along with his (comically futile) tendency to address Heathcliff as a fellow land-owning gentleman — suggests that he either leads a life of aristocratic leisure, or at the very least can afford to take a lengthy sabbatical by himself in the moors. If he does in fact carry on any business in the city, then he never expresses concern about letting it go personally unattended while he winters in the Grange.

At the start of the book, before this lack of definition can seem strange to us, Lockwood gets to relate some of its most memorable scenes. He arrives with a comic aura about him, a happy and only somewhat bumbling traveler wanting only to sight-see and meet interesting people. So he rambles up to the titular Heights, shrugs off a pack of angry dogs, and meets both cranky old Heathcliff and two grouchy young people who show him the bare minimum of required hospitality in a hilariously shocking parody of English etiquette. Lockwood does not know that the youths are the two survivors of Wuthering Heights’s core story, which can’t properly begin so long as he dilly-dallies within the frame like this.

And so he proceeds to his initiation via the unreal, sleeping for the first time inside the estate named after the book that invents him, and having at last his completely unexpected (and surprisingly violent) encounter with Catherine’s ghost. He awakens transformed: where a modern reader would expect this dream sequence to provide a bit of thoughtful foreshadowing, Lockwood will have none of it. Grasping the encounter with amazing literalness and immediacy, he accuses his hosts of setting him up in a haunted bedroom, causing a ruckus that ejects him back to the Grange filled with impatience and confusion. Awakened to the suspicion that he has managed to wander directly into someone else’s story, he summons his rental’s housekeeper to take breakfast with him and provide some expository gossip. Thus does the kind and chatty Nelly wind the clock back 30 years to properly commence the main narrative of Wuthering Heights, a layer she continues to command for almost all of the book’s remaining pages.

Throughout this truer telling, Lockwood fades into near-invisibility, but makes an effort not to disappear completely. By way of short interruptions that mark the passage of time in the outer frame (and acknowledge that Nelly’s long tale would realistically require a number of sittings to unfold thoroughly), he attaches a keep-alive ping at the start or end of the occasional chapter just to remind you, dear reader, of his continuing existence. A medieval cloister-dweller casting the shadow of his personal presence now and again in the marginalia of the other-authored work he otherwise transcribes with dutiful fidelity.

This leads us to what I found the novel’s most surreal moment, far moreso than its supernatural kick-off. Lockwood uses one of these breaks, at the end of the thirtieth chapter, to announce that Nelly has concluded her story. Then he says this (referring, at the start, to his medical excuse for lounging about in the Grange listening to Nelly’s recitation for several months):

Notwithstanding the doctor’s prophecy, I am rapidly recovering strength; and though it be only the second week in January, I propose getting out on horseback in a day or two, and riding over to Wuthering Heights, to inform my landlord that I shall spend the next six months in London; and, if he likes, he may look out for another tenant to take the place after October.

“My landlord”, of course, refers to Heathcliff, the protagonist of the story we’d just spent the last two hundred pages soaking in. So much time (and space) has passed since those initial, Lockwood-narrated scenes that we the readers have forgotten the common characters between them and Nelly’s otherwise stand-alone story, including but not limited to Heathcliff. I found this profoundly unsettling! Wuthering Heights has reached an ending, and — very much evoking Inland Empire, for me — Lockwood looks around and discovers himself on the set of the film he thought he was merely watching. And the cameras keep rolling.

But our man has had a long recuperation since his mind-bending encounter with Catherine’s howling shade, and so he not only takes this in stride but treats it as a singular opportunity to dig into the story he’s enjoyed so much. With the very next page, we find him visiting the setting of the novel that was just read to him and also within which he finds himself resident, and proceeds to interview the characters. Back into his comfortably default mode of a comical tourist, he even makes a little secret mission out of it, trying to discreetly deliver a letter from Nelly to Cathy, and of course fouling it up utterly. He similarly fudges an attempt, as the possessor of privileged information — having read the book, and all — to improve relations among the three, only goading them to peck and sting at one another further.

He leaves them in short order, frustrated, holding nothing more than an idle and knowingly ridiculous fantasy about running away with Cathy. Some might have ended it here, gone back to London and written fanfiction where they shipped themselves with whomever they wished, but that doesn’t suit our Lockwood. If it’s his lot to manage both ends of the frame-story sandwich, then he’ll do it right. And so, he arranges a reset.

Wuthering Heights’s concluding chapters form a recapitulation of its own preceding structure, in miniature. Again, in a date-stamped opening, Lockwood arrives at the Grange for flimsy reasons, and then immediately picks his way over to the Heights with a mind to say hello to Heathcliff. Again, he spies Cathy and Hareton within — but doesn’t bother trying to interact with them, knowing better than to try. Instead, he skips ahead to find Nelly, who cheerfully foregrounds herself one last time to relate the story of her former master’s end in the face of the childrens’ revolt.

And again, Lockwood experiences transformation through a ghostly visitor, but all sideways this time. He does not personally witness the final appearance of Catherine’s restless spirit; he merely hears about it, now holding hands with Heathcliff’s, as part of Nelly’s recited epilogue. And then something strange happens: Cathy and Hareton return to the Heights from their walk together, and Lockwood, seeing them again through the window, feels “irresistibly impelled to escape them again”. Lockwood and Cathy have become mutually immaterial to one another, and rather than having a bloody, screaming battle through the window as happened with Cathy’s mother, Lockwood plays it much more subtly and makes himself vanish from both that window and the whole of Wuthering Heights, now set to rights, forever.

But he holds onto Wuthering Heights for just a little longer, drifting over to the gravestones of all its fallen characters. In this very deliberate setting Lockwood accepts his own final reward, dropping the mic with his unforgettable line about sleepers in that quiet earth. Lockwood out. Only then does he let himself join the departed, dissolving with finality into the oblivion of “London”, beyond the book’s dream-gauzy perimeter. He has come a long way to get the last word in with both elegance and scenery-chewing, as befits his self-image. Even if it did take him two tries.

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.