You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

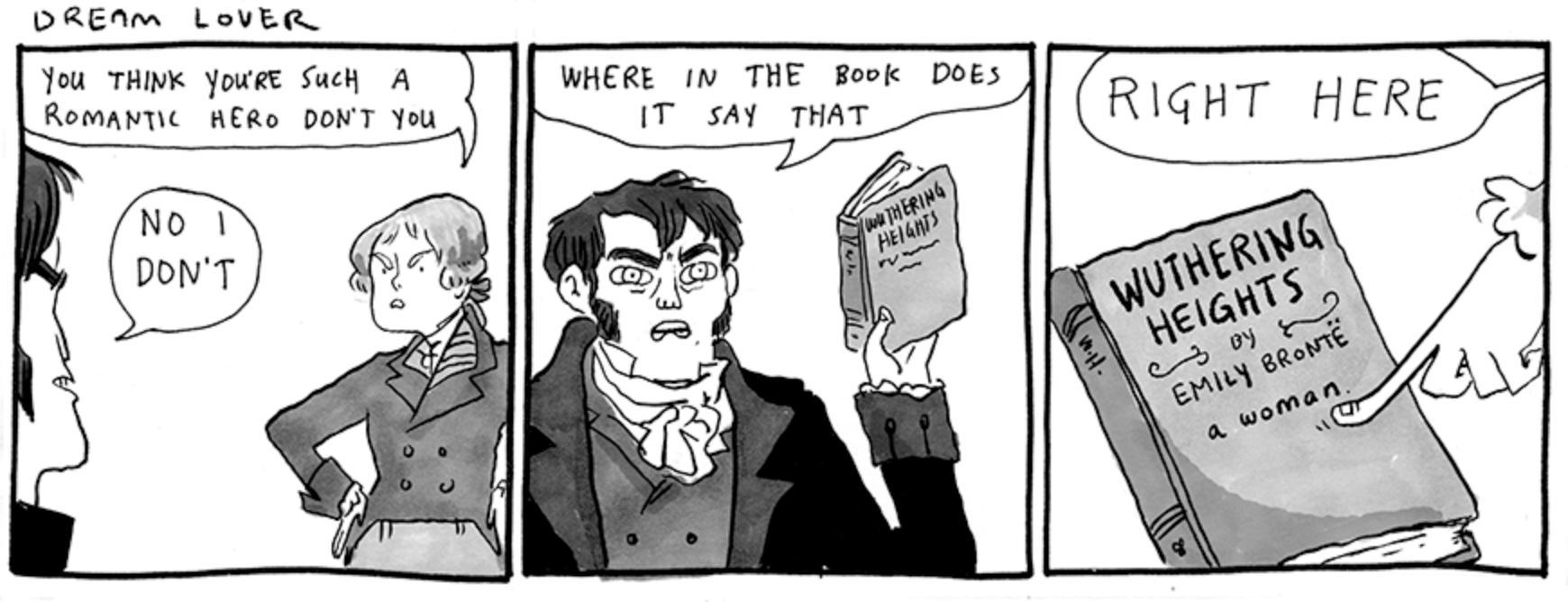

Immediately after finishing my first read-through of Wuthering Heights last month, I cursorily sought some low-hanging modern responses to the novel. I had my eye out especially for readers who, like me, had mixed feelings about Cathy and Hareton pairing off at the end. Instead, the most common immediate reaction I found came from those who read the book expecting a gothic romance, and instead got… whatever Wuthering Heights is. In the preface of the 2003 Penguin edition I read, Lucasta Miller recalls how she eagerly started into the book at age twelve, fresh from seeing the 1939 film adaptation — which veers quite a bit from its source. She ended up shocked and confused at reading not the romance she wanted but the biography of a monster.

Since that classic-Hollywood treatment elides literally half the novel’s major characters (largely by dint of nobody having any children over the course of the story), Laurence Olivier’s version of Heathcliff can manage only half as much horribleness as his textual original. He fills in the gaps with rather vanilla romantic tropes of love spurned and regained, tidily resolved within a hundred-minute runtime. Its producers chose to streamline the story by making co-protagonists of Heathcliff and Catherine, and so the movie ends when she does. The book, however, belongs solely to Heathcliff, and not only gives him a richer and deeper existence while Catherine lives, but follows his obsessed and calamatous descent into vengeance afterwards.

I’ve read references to how Brontë worked contemporary notions of gothic horror into Wuthering Heights, and assume these often refer to its surprising incorporation of the supernatural. But, as a reader, I found myself more literally horrified at Heathcliff’s personal transformation over the course of the novel. He speaks true when he proclaims that he and Catherine are one, in that her death makes his own living heart rot away. He becomes a sort of high-functioning undead, burning with hate at everything around him that dares to remain alive, seeking to punish every such life around him with a state of subjugated wretchedness.

A month ago, only about halfway through the book, I wrote this:

The novel, let us be clear, is hilarious, describing one outrage or misadventure after another befalling two little families living in the moors after a howling outsider, the earth-elemental named Heathcliff, crashes into their sleepy orbit and upsets their equilibrium for generations. I have laughed out loud with shock and joy several times so far.

I stand by this description of my experience, certainly. Early-novel Heathcliff, young and powerless in a world he didn’t make, can only sputter and fume with knee-slapping impotency about all his frustrations. This culminates in perhaps my favorite moment in the early story (and one which very much does not exist in the 1939 film), where Hindley’s drunken attempts to stab Nelly in the face makes baby Hareton go flying over the bannister. Heathcliff happened to be pacing around and grumbling downstairs at that moment, and absent-mindedly caught the baby before realizing the situation. This makes him fly into a rage at yet another lost opportunity for bloody vengeance! This may have been the point at which I had to put the book down and write a Fogknife post.

But boy, did I stop laughing once I got deep into the latter half, with a fully empowered Heathcliff meting out his long-awaited revenge on the two families’ next generation. Not satisfied with merely assuming ownership of both their estates, he completely destroys the lives of two children, and makes a game attempt on a third.

The most chilling passage in the book, to my eyes, arrives in chapter 21. Heathcliff, having played a long con to become Hareton’s foster father, gloats at length to Nelly about how he has carefully and cruelly stunted him with intellectual deprivation, teaching him to value incuriosity and dullness — and all so he can imagine how much disgust this would bring to the boy’s father, were he only alive to see. He cackles that Hareton has become “gold put to the use of paving-stones”.

In the same passage, he dismisses the similar project applied to his own son, Linton, as “tin polished to ape a service of silver”. Linton spends his short life a dissipated weakling under Heathcliff’s direction, unwittingly wasting his potential as much as Hareton does. We get the sense that Healthcliff sees him a mere tool to secure his ownership of the Grange and the erasure of its former occupants, with no value afterwards. Healthcliff ultimately lets him drop dead, literally, so he can return to his passion-project of continuing to torture his memory of Hindley via Hareton. One isn’t sure which of the two boys represents the greater tragedy.

As difficult as I found it to swallow, Heathcliff’s true monstrousness made me love this novel all the more. The fact is, I hunger for more truly horrible villains in my fiction. I feel done with comic-book bad guys who don’t even try to elicit negative feelings from their audience. Nobody really hates the Joker, or Cobra Commander, or Ernst Blofeld, despite their claims to “evil”. Sure, Darth Vader blew up a planet, but he never once boasted about how much pleasure he took from it. Nor did he stretch its destruction out over a decade, chortling as he watches each life destroyed in slow motion, and composing fanciful similes about his enjoyment.

The true “OK, this isn’t funny anymore” moment arrives when Heathcliff makes his big mistake, trying to exert control over young Cathy, the last remaining free character in the tiny world of Wuthering Heights. With her already grown into young womanhood, he can’t simply suffocate her mind as he did to the boys, so he resorts to tricking her into imprisonment, and then beating the crap out of her. He slaps our dear narrator Nelly to the floor too, and he may as well have reached out from the pages and cracked me one across the cheek.

(This comes several chapters after Isabella flees her hateful husband with little Linton. She merely intimates in her letter to Nelly the regular violence she withstood under Heathcliff’s hand, which sets up as possible this future scene with Cathy and Nelly, while keeping the full, horrifying force of it bottled until then.)

Heathcliff’s “shower of terrific slaps” jolted me the same way that The Shining’s ghosts dropping n-bombs did. “OK, it’s one thing to drive a man to axe-murder his family, but you don’t have to be racist about it” on the one hand, and “Sure, you can forcefully waste two young lives in order to show up long-dead aristocrats who pissed you off as a kid, but did you have to punch a girl” on the other. It left me shocked and unmoored and very ready for the ensuing chapters where Cathy accepted her situation, gathered up her patience, and used her undulled wits to convert Hareton and then destroy Heathcliff. I felt all too happy to have the book end with that particular unquiet sleeper finally taking his long-sought place in the cold and crumbling arms of his other half.

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.