You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

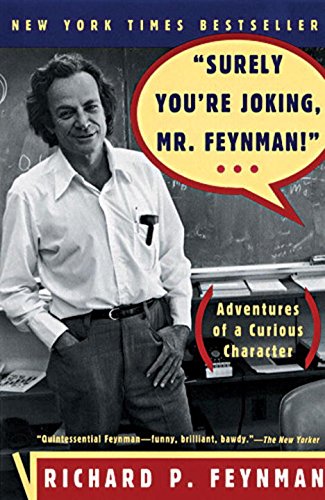

The idea to reread this collection of Richard Feynman memoirs, last read around 1997, probably took root a few years ago after watching the Feynman lectures that appear in The Witness. Not sure what finally moved me to take it off the shelf, but I feel so glad I did. Reading these stories fresh out of college entertained me; today, most unexpectedly, they energize and inspire me. I feel called to emulate Feynman’s deep curiosity about the world around him, his impatience to accept the surfaces of things, and the joy he expresses in diving as deep as he can, again and again.

Despite all the changes wrought in me and in the world since the last century’s end, the stories here hold up so well — even if some feel like they want a few additional contextualizing caveats. The collection dates from 1985, and a deft preface in more recent editions could serve as the missing apologia, acknowledging and preparing the reader for the hairier bits. (Amazon suggests that the latest edition, from 2018, has a new foreword by Bill Gates — who, eh, is not who I would have picked.)

Very aptly subtitled “Adventures of a Curious Character”, Surely You’re Joking collects essentially episodic adventures — albeit sometimes loosely glued-together, based on long conversations recorded by biographer Ralph Leighton — that follow Feyman catching a whiff of some topic and then throwing himself wholly into its investigation through personal practice, sometimes occupying months or years of his time.

My favorite may be the chapter “O Americano, Outra Vez!” where a chance conversation with a hitchhiker about South America leads to Feynman landing an academic guest-post in Brazil. After immersing himself in Portuguese, he takes every opportunity to explore the streets of post-war Rio de Janeiro, where he falls for the local rhythms so utterly that he winds up in a samba band as its novelty-foreigner frigideira player. (He misses the beat so often in practice that his bandmates make a catchphrase of “the American, again!”, giving the chapter its title.) The band goes on to dominate a local competition, then completely falls apart at the grand Carnival.

Feynman relates the entire adventure, and many others like it, with such soaked-through joy and even gratitude, the tales of a man who wrung every drop from the life given to him. Maybe I had to be a little older to appreciate it as such! Crucially, while the stories are often instigated or informed by his “day job” as a renowned physicist, they all make clear that one needn’t be a genius to open up the world the way Feynman does. His stories are driven by curiosity and the will to explore, and not by cold intelligence.

And so importantly, the Feynman of these tales is honest to a fault. Never once does he describe himself deceiving anyone, and he remains always forthright about his intentions to anyone who asks. The one story in Surely You’re Joking where unvarnished truth presents any obstacle has Feynman seeking companionship after the war, and finding that coming in hot with stories about how he worked on The Bomb would quickly end any first date — because it made him sound like a damn liar! So he switched tactics to admitting he worked as a physicist for the government during the war, but didn’t want to talk about his specific project. Of course, this accidentally gave him an air of mystery, and thus yet another thing he could have some fun exploring.

This leads into the difficult material. I knew going in, both from memory and from encountering more recent critiques about Feynman’s autobiographies and reputation, that Surely You’re Joking has a gnarly chapter where he employs shockingly sexist language. Titled “You Just Ask Them?”, it recalls his introduction to pick-up artistry under the tutelage of a sybaritic mentor in 1940s Las Vegas. Feynman dives into the lessons with his usual fervor, taking the mentor’s advice — just as applied by “PUA” creeps today — to denigrate the women he has his sights on, starting in his mind. So in his honest accounting of this adventure, he recalls his mental frame of seeing all the women in the venue as a bunch of selfish bitches.

By the end of the chapter, Feynman grows uncomfortable with this approach and abandons it. He begins to instead practice a sort of degenerate form: he engages in his usual singles-bar socializing, and then one drink in asks “Say, do you want to have sex later?” Naturally, he finds this method to have at least as high a hit-rate as the louche’s approach, with none of the high psychological costs to either party. While I love this memorably sex-positive twist ending, those earlier words still sit right there on the page, and I recognize them a real hurdle to the modern reader — just like the fact that young Feynman, however briefly, thought that the whole sordid business was ever worth trying in the first place. And then elderly Feynman laughs the whole thing off! If he expressed any regrets about his 1940s behavior, his 1980s biographers chose not to include them here.

These young-and-thirsty stories to one side, I would describe the older, story-telling Feynman’s attitude towards women as “genial, if not progressive”. He names, without special remark, various women as his colleagues in stories set decades after the war. He also never remarks upon the complete absence of female scientists in his college, wartime, and mid-century adventures, casually using gender-exclusive language throughout these recollections. I don’t see any ill-will here, but rather the specific blindness of a man whose society just doesn’t teach awareness of certain sorts of systemic inequalities to the same degree that mine does.

In this vein, Feyman struggles both in his stories and in his story-telling with the notion of relative social-power levels between people, including those between influential men and their female subordinates. In his latter-career tales as a Nobel Prize winner, Feynman expresses painful awareness of his own celebrity status, regarding it as an obstacle to work around. But then he’ll recall how, during his deep dive into figure-drawing, he would ask female undergraduates to pose nude for him, and they’d often agree, and how surprising and delightful that was: the power of asking nicely! And the modern reader wishes to say: come on, Dick.

So, Surely You’re Joking offers memoirs by a man of his time, through and through. I finish the book convinced that Richard Feynman made his very best use of all the gifts granted him, within the society that molded him. I would absolutely recommend this collection of amazing grandfatherly tales to a modern reader of any age — so long as they are willing to have a charitable heart for filling in the now you see, back in those days explanations missing in this telling.

This article was also posted to the “books” section of Indieweb.xyz.

Next post: I like date-based version numbering

Previous post: Jots, scraps, and tailings, a new microblog

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.