You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

According to my archived receipts, I ordered a copy of Samantha Mooney’s A Snowflake in My Hand in April of 2013. I cannot remember how I found this particular title, but given the timing I surely purchased it as inspirational fuel for a never-commenced project, a followup to 2010’s The Warbler’s Nest that I’ve long thought of as “the sad cat game”. This also means that it would have shown up at my house right around the time my parents’ health crisis began, kicking off an immensely challenging half-year that reset all my intentions and priorities. So I did not read this book, let alone make the game.

According to my archived receipts, I ordered a copy of Samantha Mooney’s A Snowflake in My Hand in April of 2013. I cannot remember how I found this particular title, but given the timing I surely purchased it as inspirational fuel for a never-commenced project, a followup to 2010’s The Warbler’s Nest that I’ve long thought of as “the sad cat game”. This also means that it would have shown up at my house right around the time my parents’ health crisis began, kicking off an immensely challenging half-year that reset all my intentions and priorities. So I did not read this book, let alone make the game.

These Covid times, however, have found me dipping into my personal library — specifically, that fraction of it that has traveled with me over the years, sometimes across a dozen house-moves or more, surviving the printed-matter cull that each one involves. Snowflake has racked up four points on this particular board. After I had visited with some much older friends from my bookshelves, this slim volume pulled at in my attention. While I still have no plans to make the cat game, our world’s pervasive melancholy plus the recent passing of Shadow, my brother Ricky’s cat, guided me to read this book at last.

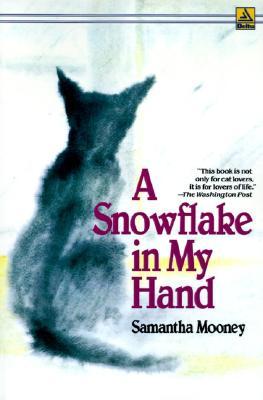

The title comes from a poem framing the book, a verse-memory of the author’s favorite cat: Fledermaus, a runty, harelipped all-black that briefly served as mascot for the New York veterinary clinic where Mooney worked in the 1970s. Her prose is significantly blunter than the book’s evocative title or the haunting watercolor she painted for its cover, depicting little “Maus” gazing out a rainy windowpane, on the verge of fading into the gray air herself.

But the book isn’t really about Fledermaus, or even Mooney’s loving memories of her. Maus’s brief life flickers through the middle pages of a strictly chronological recitation of an eventful year or two in the author’s life. One month follows another, down through the chapters, and for each one she describes all the people and animals that happened to have passed through.

The narrative locks its focus on its cats, both the ones in Mooney’s home and the feline patients at the clinic. The patients’ owners receive secondary attention, and every other human subject — Mooney’s friends, colleagues, and even herself — stay in the background. The author describes her own role so slightly, in fact, that it took some reading before I realized she was not a doctor but a junior technician, taking a half-load of undergraduate courses alongside her clinic work, and moonlighting in a restaurant as well.

Snowflake’s log-book approach offers some tantalizing glimpses of a young woman’s life in New York during the 70s. I squinted to pick out details about the apartment she rented, and the friends who sometimes crashed there. At one point she and Fledermaus vacation at “The Playboy Club” in New Jersey, a detail that reads rather bizarrely today! A minute of online research showed how this was a resort hotel that ol’ Hef did indeed build in the freewheeling 1970s, and which lost its branding at the start of the Reagan era, and has since gone to seed.

The narrative ends when Mooney notices that an emotionally intense period of life, growth, and death among many people and animals dear to her has come to a close, letting her drift into a period of quiet reflection she didn’t realize she needed so badly. This reflection becomes the text of A Snowflake in My Hand, concluding with the latter half of the opening poem: aching to hold a tiny loved one again, a sweet memory that can only melt away when grasped.

For all the workmanlike recollection that comprises most of Snowflake, it does contain a nicely subtle structural turn, opening with a study of what “quality” means to veterinarians, and closing on how the same word applies to their patients and clients.

To the healers, and especially those who focus on often terminally ill animals, “quality” means quality of life: the thing they try hardest to maintain within their patients, and the presence-or-absence of which directs all their actions. Mooney gets quickly into hard decisions that the clinic’s staff and clients must make about the patients — not just when to end an animal’s life, but when and how to extend it. An early scene relates how a client and a doctor surprised one another as they decided together to amputate an 18-year-old cat’s disease-ruined leg, rather than taking the more typical route of euthanasia. An otherwise robust old cat, it rebounded and adapted quickly once the source of its suffering vanished, and it lived joyfully for three more years.

(The book counterweights this happy story with a profound scene some chapters later, where Mooney briefly revives a terribly ill cat with a transfusion, letting it enjoy a single day of comfort and affection after a long misery, and before a peaceful, guided death.)

At Snowflake’s end, Mooney revisits “quality” in another sense, as in the many qualities that make up a personality. The work a person puts into keeping a pet healthy and happy, she writes, becomes energy invested into a long project. Seen this way, a long-lived pet exists largely through the exercise of its human companions’ personal qualities. And in those cases where a pet outlives its owner — as happens in one of the final events of this book’s recollections — it continues to serve as literally living evidence the departed person’s quality, their goodness and care, for the rest of that animal’s time.

I don’t have any good photographs of Shadow, but she’s easy to describe. You’ve met her type, probably: a gray blobby homebody quite content to move very little. This is how she spent the latter seven years of her life, meatloafing in Ricky’s one-bedroom apartment in Bangor.

She had a deep memory, and would bellow a greeting at me every time I visited Ricky for the first time in a while. Ricky felt an especially deep rapport with the cat; he’d often talk to her late into the night.

Before living with Ricky, Shadow was our parents’ cat for more than a dozen years. I came to understand that Ricky saw Shadow as the last living link to them. When middle-brother Pete suddenly died earlier this year, Shadow became the only nearby family that Ricky had left. And now she’s gone, too.

Ricky was close to Pete, and his untimely death upset him as much as you can imagine, but he worked through the pain swiftly. Shadow’s long-expected death, literally in his arms, crushed him. It haunts him still, many weeks later. These days I have two scheduled phone calls per week with Ricky, and he describes every time in his Down East dialect how he misses Shadow “something awful”, in the way he used to talk about missing “maw” and “pop”.

Ricky has singled out a particular large stone on the banks of the Penobscot River, within walking distance of the apartment where he now lives alone, declaring it Shadow’s Rock. He goes there frequently to remember Shadow, and imagine her presence as a little nearer somehow. I know that he means this literally: it really is the departed cat that he turns his mind to. But I understand better, now, all the passed-away he remembers at once via lazy gray cat, that accidental inheritor of all quality from our diminishing family.

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.