You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

My final Sandman post for the time being, having listened to all 25 currently published hours of Audible’s radio-play adaptation of this personally formative comics epic. (If they produce more episodes in the future, I reserve the right to write more about it. I do not foresee myself giving the same treatment to the upcoming television adaptation.)

As always: this merely records my own reactions to this dramatization of a personally beloved printed work, and does not strive for any objective or thorough review of its content.

A Game of You

This is the first Sandman arc that I read in its original, monthly, serialized format, rather than as a tidily bound collection. Like Season of Mists, I didn’t remember it very well, but for a wholly different reason: I never really had a chance to re-read and savor it as a whole work. Each issue ended up in the trash shortly after I read it, alongside every other used-up periodical in the house. (I was 17; I didn’t make the rules.)

Since I never owned the collection, I thought very little of purchasing a digital edition on Comixology before cueing up these Audible episodes. It took the work of just an evening or two to absorb. How much shorter it seemed than it did in my memories, where reading the whole work took half a year!

My confession: I wish I hadn’t done this, at least not before listening. A Game of You is a terribly sad story, the first real tragedy of the greater Sandman epic, with losses that feel much more profound than the gruesome deaths that pepper the earlier stories. Experiencing it twice so rapidly in two different formats left me utterly exhausted. My fresh exposure to the original material also made the adaptation’s divergence from the printed text stand out all the more, and some of these creative decisions didn’t sit right with me.

I feel a lot better equipped today to appreciate the themes of this storyline. Just as its title suggests, A Game of You plays with shifting, slippery, uncertain identities, both mundane and fantastic. Its includes a lesbian whose one-night stand leaves her pregnant, a scene where three womens’ individualty blurs as they adopt an aspect of triple-bodied Hecate, and an antagonistic dream-creature who colonizes and subsumes the childhood memories of unwitting sleepers.

And then there’s Wanda, a fiery transwoman who knows precisely who she is, but roils with subconscious anxiety that she hasn’t gone far enough to claim it. The radio play excises this quality from her, leaving her contribution to the theme as—just being transgender, I guess?

I understand the reason for the change. The comic explores Wanda’s fears through a focus on the particulars of her anatomy in ways that may have seemed sympathetic 30 years ago, but come across as distasteful today. In this adaptation, Wanda’s nightmares about operating rooms carry additional narration stating outright that she has a generalized phobia of medicine, for no particular reason. Her conversation with Dead George about the old gods’ gender essentialism remains, but with the dialogue rebalanced to give Wanda a lot more say, and to suggest that George is merely an ignorant troll rather than a truth-speaker from beyond the veil.

Alongside her neighbors Hazel and Foxglove, Wanda feels very dear to me. The three women may have been the first openly queer characters presented to me in new fiction with wholeness and respect, instead of an invitation to gawk or laugh. And coming in from a fresh re-read, I couldn’t help feel that poor Wanda, who already loses so much in this story, would have even more taken away from her by this radio play.

One particular change around Wanda felt particularly sad. In the final chapter of the comic story Barbie briefly humors Wanda’s aunt by using Wanda’s birth-assigned gender in conversation. But as soon as she starts speaking candidly and from the heart, she reverts back to Wanda’s correct identifiers—an act of love, more than mere defiance. The older woman, touched by Barbie’s sincerity, stops “correcting” her for the moment and comforts her instead. It’s a subtle, powerful moment.

But the radio play removes this as well. This version of Barbie doesn’t give Wanda’s aunt an inch, refusing to recognize (what we would today call) Wanda’s deadname, and pushing every wrong-side-up pronoun back at her—the way we’d expect any true friend in the twenty-first century to stand up to a closed-minded attitude. This makes a fraught scene much more palatable to modern listeners—and it’s poorer for it.

Look, A Game of You isn’t even about Wanda; my hangups about her treatment here are really just an expression of my exhaustion with the way I mishandled my own exposure to it. This story means a lot to me, and it’s so much sadder than I remembered, and the radio drama preserves that well enough that I cried a little at the end, despite all my misgivings.

Barbie’s final lines, spoken directly to the reader, echo profoundly through time, and through the three decades of lived experience that now separate she and I. Or rather, the kid I was when I first read her story, and the person I am now. She and Wanda and Martin Tenbones and all the others have been part of me, all this time, and that’s why I wanted to listen to all of this in the first place.

On the other women:

Hazel’s voice actor turns in a great performance, sounding just like I’d imagine her. Foxglove’s actor punches her up with a New Yawk accent which I did not hear on the page, but I will absolutely allow, and I hope to hear more of it should this play roll into Act III.

Hazel’s ignorance about how babies are made must make her look like a goddamned idiot to modern young listeners or readers. I half-expected Gaiman’s narrator-voice to wander in with a reminder that the non-existence of the internet only begins to describe the cultural and knowledge gaps a marginalized person faced in 1991 that they would not have today.

I really admire how the story presents Thessaly to us as a sexy-nerdy witch—the radio play includes new narration suggesting that the listener probably knows a Thessaly, all mousy hair and big glasses and art-history books—and then slowly reveals her as so witchy that she is no longer entirely human. We naturally assume her motivation for hunting the Cuckoo is to save Barbie, but we come to learn it’s actually because she sees the Cuckoo as a potential threat to her own unnaturally extended life. She does not care about any collateral damage she might wreak in her quest, and ends up directly causing mass death and destruction across two worlds—all because a bird looked at her funny one time.

On that note, and for the second time in this Audible-driven re-read of The Sandman, I found another Watchmen nod: this time, to a side-story of an unlikely friendship that forms between two (or three) dissimilar characters, and who at the height of their bond are slain in a stroke by an apocalypse pulled onto New York City by a monomaniacal antihero. Huh.

I just this moment understood that during their little moon-walking trick, Foxglove, Hazel, and Thessaly respectively repeat the Maiden, Mother, and Crone theme that echoes down the whole length of The Sandman—though you wouldn’t know it to look at any of them, as is the intent. Morpheus himself recognizes this, and drops a clue when he calls Foxglove “little maiden”. And that seems pretty weird, in the moment! “Maiden”? According to whose definition, exactly? Well, the same inflexibly ancient ones that wouldn’t recognize Wanda as a woman either, says George. All their empires long since reduced to the blowing sands that make the Caliph shudder, a few stories downstream.

The Hunt

Great story. I’m laughing as I type this! “Great story,” after all of the above. Okay. Well, it is.

Definitely my first encounter with the idea of Baba Yaga in any medium.

Given the adaptation’s willingness to sand down dicey language, I was a little surprised it kept Grandpa’s old-world muttering about Gypsies and Roma and Jews intact. But he also rants about Michael Jackson and so on, so, who listens to him anyway.

The Soft Places

As delicious as any other example of secret-history fiction found in The Sandman.

This story and the next one concern residents of The Dreaming passing the time out of earshot from Morpheus, casting wry judgment on his new girlfriend without dropping her name. Oh boy, do I ever recall the fun my online friends had speculating about this mysterious woman’s identity! An early and joyous communal fan experience, for me.

The Parliament of Ravens

So good.

With this episode and the next one, the adapted Sandman feels like it’s celebrating its own conclusion-for-now, having a bit of fun with its own theme song: this time, having it play from baby Daniel’s toy music box.

Little Daniel and Goldie cooing at each other in the comic is adorable but the effect here, performed by adult actors talking like pre-verbal babies, is just a bit hard to listen to.

Ramadan

A big reach here: this adapts the 50th issue of The Sandman, printed after the Brief Lives arc. But Act II clearly wanted to go out on a high note, just like Act I did, and we have to allow it. The theme song sidles in with a magnificently corny Arabian kick.

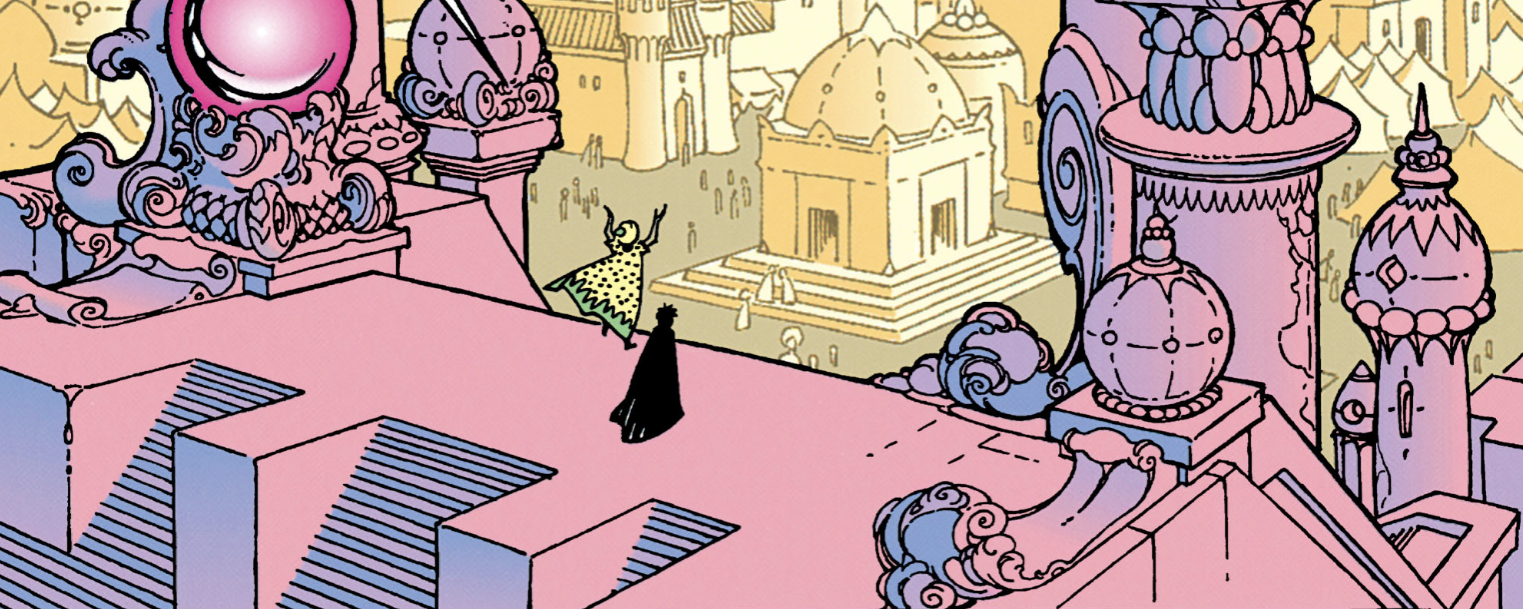

Ramadan might contain my very favorite artwork of any single Sandman issue. This time, I do not regret refreshing my memory first. Not that I needed to—I have much more clear recollection of buying and savoring this single issue in my university dorm room, years after A Game of You began. Truly a treasure.

My only note about this marvelous adaptation is its completely understandable choice to leap clear over a certain eyebrow-raising panel from the comic’s earlier pages, not even trying to retune its text—the only time the otherwise panel-faithful play does this, to my recollection. Unlike other omissions I have mentioned, this one does not diminish the tale at all.

I don’t expect I’ll have to much else to say about The Sandman for a while. I had a good time writing these last half-dozen articles. If they whet your appetite enough to pursue any of the referred work, I hope you enjoy reading or listening to it. While neither is flawless, especially as they communicate across a thirty-year gap, this comics series is very important to me, and taking in this lush and quite unexpected audio adaptation has made me feel happy, and fortunate.

Next post: I’d like to hear you say your name

Previous post: Notes on The Sandman: Act II (Eps. 1-11)

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.