You have just read a blog post written by Jason McIntosh.

If you wish, you can visit the rest of the blog, or subscribe to it via RSS. You can also find Jason on Twitter, or send him an email.

Thank you kindly for your time and attention today.

I enjoyed describing the earliest Nexus stories in my last post, and my month-long move to New York has meanwhile remained in-progress: I’ve accomplished little aside from more packing, filling out more rental forms, and reading more comics in my downtime. So here’s thoughts on three more of the many comics I’ve been into lately. (I read all these via Comixology, and I bet you can find one or more of them at your local public library too.)

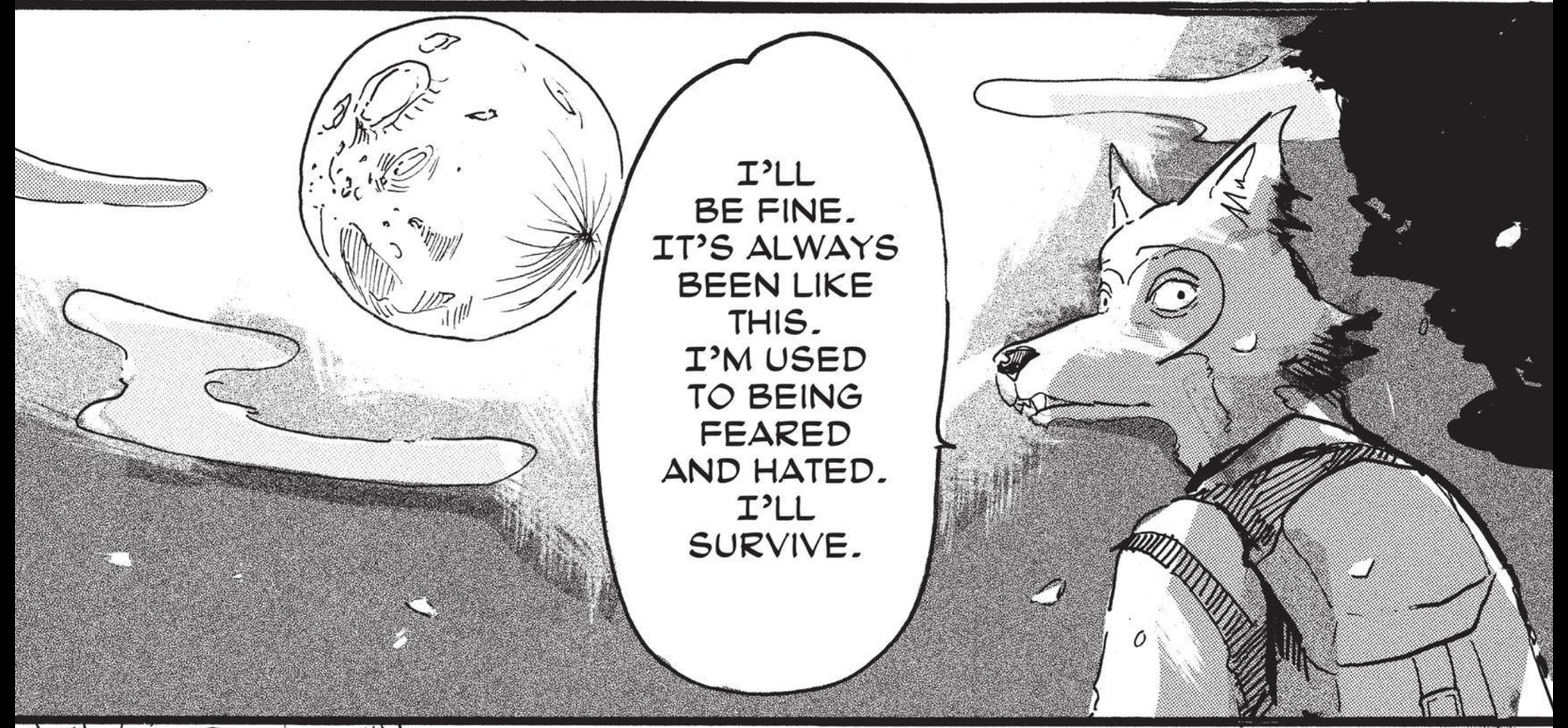

Paru Itagaki’s manga Beastars delivers a Japanese high-school melodrama in a world like Zootopia’s, presenting all characters as different anthropomorphic animals, and allowing their often-conflicting beastly attributes to drive the story.

The protagonist, a lanky and moody gray wolf boy named Legoshi — named, according to the book’s end-notes, after Bela Lugosi — deals with foils such as the self-destructive prima donna who runs the school drama club, and the girl with an unseemly level of sexual agency who won’t leave him alone. Both of them happen to belong to edible species, leading in turn to oh such pained internal struggles.

Furthermore, we get to know Legoshi only after an anonymous but distinctly wolf-shaped lurker opens up the very first issue by killing and eating a student. This book takes a little bit of run-up to find its real pacing, but once it gets there it’s pretty great.

I’ve read the first two volumes available in Comixology, with a third one appearing even as I wrote this post. I have just now learned that the Japanese edition of Beastars has reached 15 thick volumes in less than three years and continues to grow, demonstrating how I have no idea how manga is made, compared to western comics. It already has an animated adaptation, too, one slated to arrive on American Netflix in 2020. I can’t predict how far into this particular rabbit-hole I will drop, but I have enjoyed it so far.

Notably, with Beastars Itagaki becomes one of the only female comics creators found on my bookshelf. Not knowing anything about the comic when I picked it up on a friend’s recommendation, I was delighted to learn this, and then humbled to realize the deficit that this has highlighted in my own reading habits.

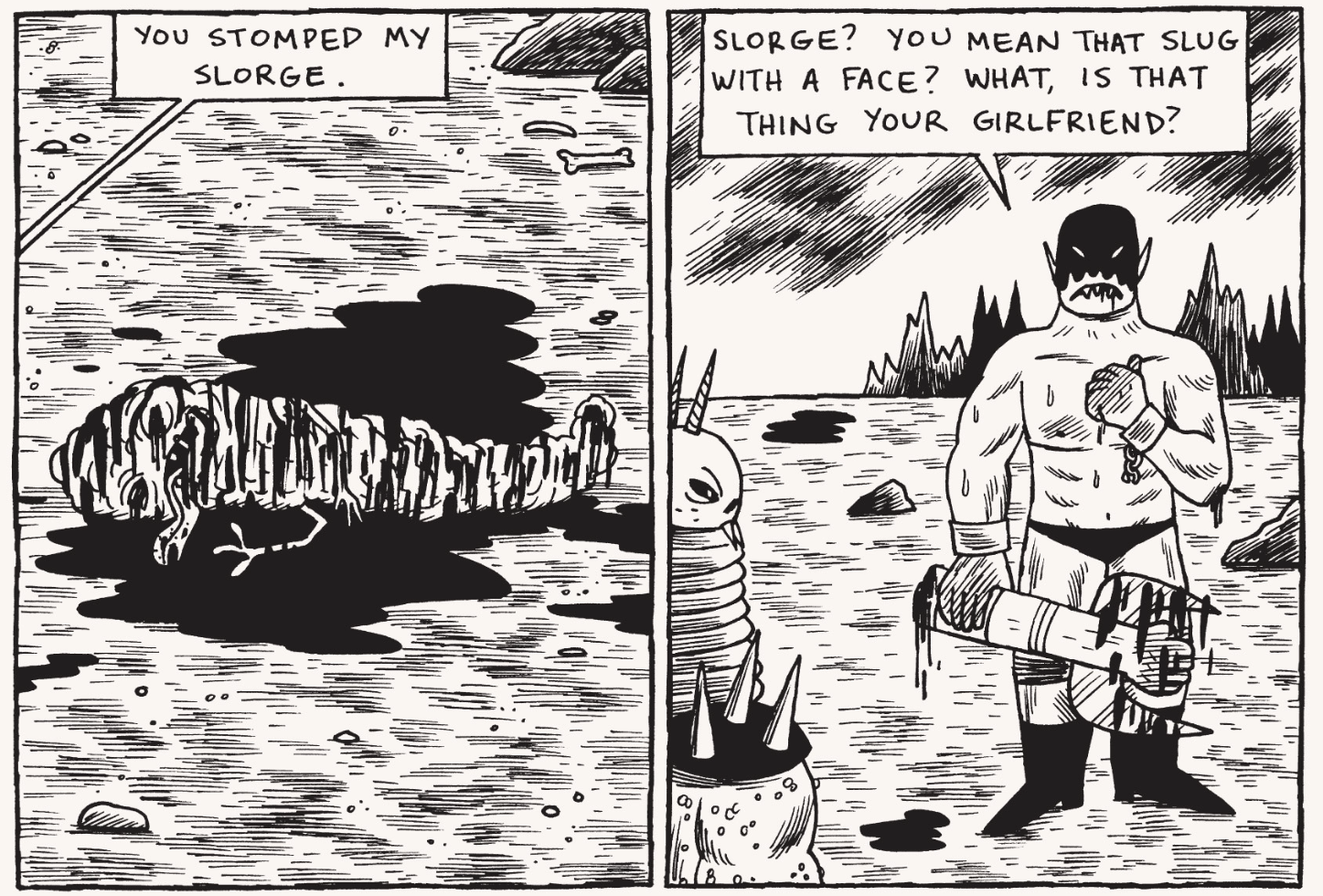

Case in point: while I also like Johnny Ryan’s Prison Pit, I could never generally recommend it. It is a sullen teenager’s notebook doodles turned into a thousand-page epic. On the surface, it follows the adventures of a gore-covered mutant with an unprintable name who rapes and murders his way through a hell dimension populated only by other rapist-murderers all trying to claw their way out. At the level of its (ripped-out, pulsating) guts, I read it as a body-horror comic fueled by a certain kind of confused self-loathing particular to adolescent boys.

More specifically, I see Prison Pit as the lurid imaginings of an angry teen circa 1986 who has been grounded without TV for mouthing off at his mother, and so sits in his room blasting heavy metal and grinding out page after page of crude revenge fantasies. The casually homophobic language and gynophobic attitudes merely flavor the comic’s real mood, an infinite fear and loathing that puberty can bring to the owner of a changing body with its own agendas. In the world of Prison Pit, girls are unintelligible monsters, other boys are swollen and threatening enemies, and their ejaculate is a ubiquitous substance of unknown purpose that powers various terror-weapons.

I date these fantasies to 1986 because I fear how the same boy in 2019 could so easily get online and become radicalized in short order by white supremacist incels. But I like the book anyway because it picks its direction and consummates it so completely. It’s something like a comic-book adaptation of the video game Doom, were such a thing done correctly, giving every speaking character the voice and attitude of the same world-and-self-hating 14-year-old boys that composed the game’s target audience. The eternally acne-scarred adolescent within me very much enjoys this really quite terrible comic book.

Prison Pit, too, has received an animated adaptation.

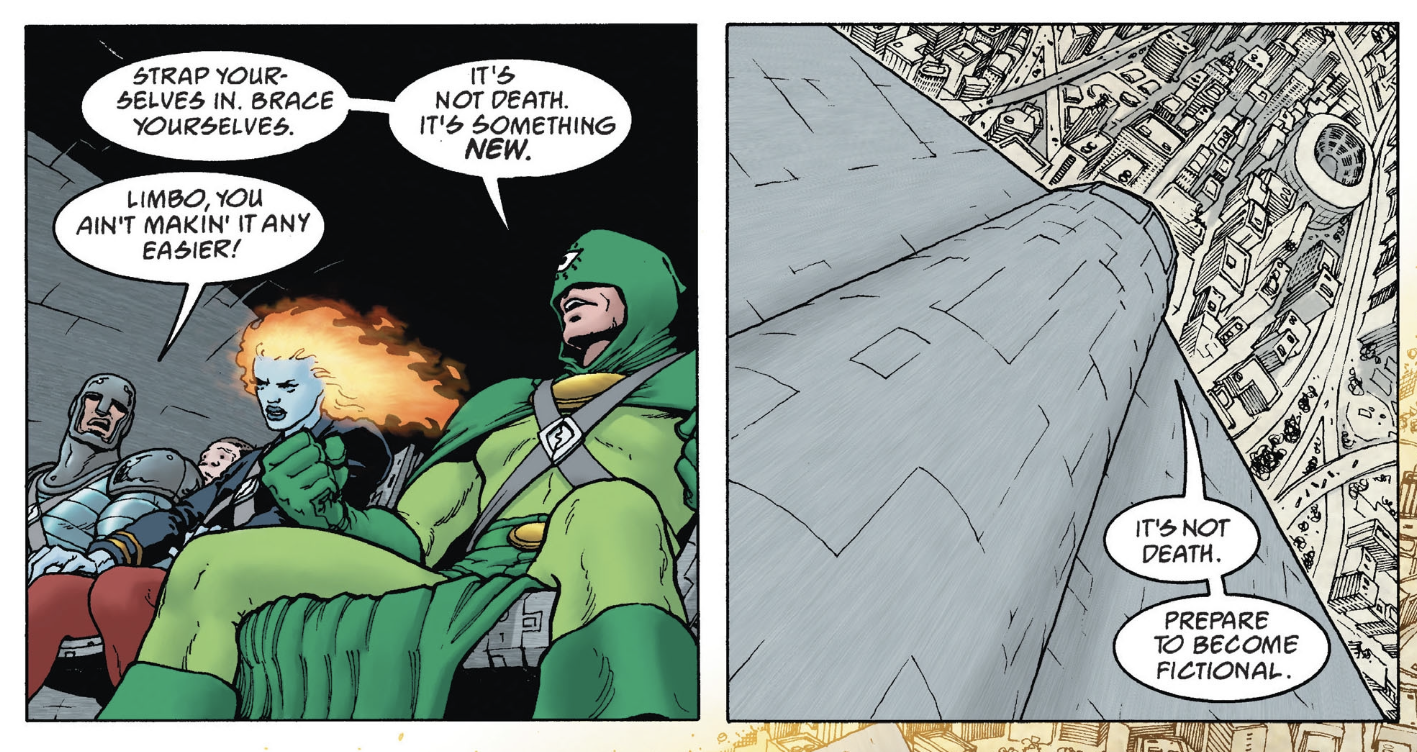

Finally, I read and loved the four-chapter Flex Mentallo: Man of Muscle Mystery, written by Grant Morrison and pencilled by Frank Quitely. I had actually purchased the first three parts as individual comics during their initial publication in 1996, but missed my chance to buy the last issue in the confusion of my first summer after graduating college. This comic is good, and meshes eerily well with some coincidental reading about contemporary cosmology that I’ve lately dipped into.

Flex Mentallo, starring one member of Morrison’s Doom Patrol crew from a few years prior, hit the stands about two years into his six-year-long masterwork The Invisibles. It shares many of the longer work’s themes of reality as an infinitely self-reflective superstructure, encouraging the reader to adopt a cosmic perspective in order to achieve transformative enlightenment. And it does this in a story about an overt Charles Atlas parody aware of (and embracing) his role as a comic-book character, with the whole thing narrated by a burnout rock star as he rides out an acid trip.

And when I put it that way, it sure sounds rather insufferable, doesn’t it? Certainly some of my enjoyment came from personal nostalgia, but I feel quite sure that this book — drawn exquisitely by Quitely, one of my very favorite comics artists — has more going for it than that. Short and self-contained, it makes for a far tidier read than the sprawling Invisibles, and I found its themes as least as meaningful and relevant today than I did nearly a quarter-century ago. I spoil nothing to say that it ends with a super-heroic apocalypse a million times more satisfying than anything that might have appeared in movie theaters recently. This is a book that asks you to look up. What joy I found, reading this lost ending at last.

This article was also posted to the “comics” section of Indieweb.xyz.

To share a response that links to this page from somewhere else on the web, paste its URL here.